Pre-trial Detention in Palma: A Prison Staff Member Suspected of Bribery — Now in His Own Prison

Pre-trial Detention in Palma: A Prison Staff Member Suspected of Bribery — Now in His Own Prison

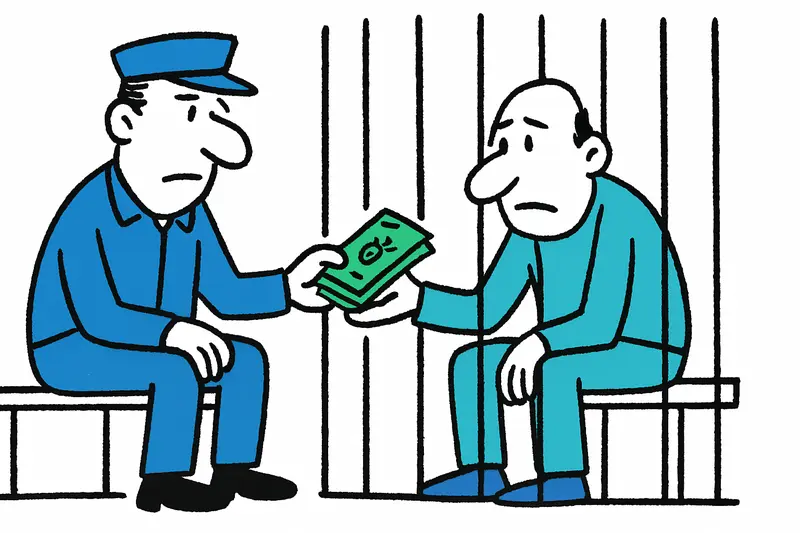

A senior staff member of the correctional facility in Palma is in pre-trial detention. He is accused of accepting money from an inmate. Notably, the judge ordered his placement in the same prison where he had worked until shortly before.

Pre-trial Detention in Palma: A Prison Staff Member Suspected of Bribery — Now in His Own Prison

How can an employee of a prison be placed in pre-trial detention — and of all places be housed there again?

A senior staff member of the correctional facility in Palma is currently in pre-trial detention. He is accused of having accepted money from an inmate. The man had already been suspended in July 2024 after it became known that he had contact with a female inmate. The judge has now ordered him to be admitted to the same prison where he worked until Thursday.

Key question: Why did the judiciary order placement in his former workplace, and what are the consequences for security and public trust?

The court's decision appears contradictory at first glance. Prison staff are part of the security system — yet when one of them becomes a suspect, tensions arise between the rule of law and organisational logic. The corrections service must ensure that investigations are independent and well-founded. At the same time, there are pragmatic reasons to house a suspect at a location that already has cell capacity and secure isolation options. How much weight these practical considerations carried remains unclear.

Critical analysis: This is not just an isolated case, as other incidents such as From Investigator to Suspect: How an Ex-Head of Drug Enforcement Rocked Mallorca show. The idea that a former employee could suddenly be housed again within the same walls raises debates about control mechanisms. Who monitors to ensure there are no secret agreements between the suspect and his former colleagues? How are signs of possible further bribery, favours or even protective structures within the facility examined, as was questioned after the Raid in Son Banya: Suspected Leader in Pretrial Detention — and What Now?? It is not enough to say the judge decided so — the public has a right to know which safeguards were put in place.

What is missing from public discourse: There is a lack of clarity about concrete protective measures for pre-trial detainees when they come from the institution where they previously worked. It is also not discussed how often internal suspicion cases are recorded at all and what consequences suspensions like the one in July 2024 actually have; cases such as the Mask scandal: Why the detention of an MP in Mallorca raises more questions than answers illustrate the wider questioning of procedural transparency. The debate too often confuses single-case reporting with structural examination, and high-profile financial sentences like Two and a Half Years in Prison for Former Finance Chief: When Trust, Illness and Oversight Collide are part of that broader picture.

Everyday scene from Palma: On the Passeig des Born a coffee drinker looks toward the cathedral and reads the headline. Conversations at the next table are not about legal details but about trust: "If someone works in prison and is accused of bribery, who does it affect first?" The answer on the street is a distrust that spreads into everyday life — in supermarkets, at bus stops, in talks with neighbours who know someone working in the justice system.

Concrete proposed solutions: First: separation of duties and locations. If a corrections officer is accused, there should be a binding rule to place them in a different institution as long as this is practicable. Second: transparent monitoring by independent oversight bodies. An external agency could review which protective measures were implemented and whether staff must avoid affected areas. Third: faster, binding internal investigations with clear deadlines — suspension alone must not be the end of administrative processing. Fourth: improved reporting and whistleblower channels with protection for informants so potential networks become visible early. Finally: financial audits and regular training to identify and prevent conflicts of interest.

These measures are not expensive technical kits but organisational decisions: staff rotation, external audits, regulated administrative leave. If institutions want to regain trust, they must show that rules are enforced — not only written on paper.

Conclusion: The case in Palma is more than a headline. It is a wake-up call: we must question the system, not just the individual. The question of whether a suspect may be placed in his former workplace is symptomatic of larger gaps in oversight and transparency. Anyone living or working on Mallorca has a legitimate interest in ensuring that state security structures not only function but are also verifiable.

Read, researched, and newly interpreted for you: Source

Similar News

Between Camera, Beach Taxi and Bierkönig: Patrick Hufen and His Love for the Island

Duisburg claims adjuster Patrick Hufen works for HUK‑Coburg by day and is a welcome guest on Mallorca's stages and prome...

Axe threat in Palma: Chase on Avenida Gabriel Roca and what it says about our streets

On Avenida Gabriel Roca a vehicle pursued another early Tuesday morning and a passenger threatened the other driver with...

Mallorca on Board: Island Companies Raise Their Flag at boot Düsseldorf 2026

From the Paseo Marítimo to the exhibition hall: Mallorca’s boating industry is using boot Düsseldorf (17–25 January 2026...

Pierce Brosnan takes time for Mallorca: wine, pa amb oli and a walk through Valldemossa

While filming the series 'Mobland', Pierce Brosnan visited Valldemossa and Palma: a lunch at the historic La Posada, a t...

Housing Shortage at the Airport: Why Palma's Outskirts Are Becoming Emergency Camps

Shacks and occupied halls at Son Sant Joan airport show that housing is lacking — families and children live in makeshif...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca