41 Percent: When the Taps Run Drier on Mallorca and the Neighboring Islands

At the end of August the Balearic Islands reported only 41% water reserves. What does this mean for Mallorca, agriculture and tourism — and which solutions are realistically feasible?

41 Percent: When the Taps Run Drier on Mallorca and the Neighboring Islands

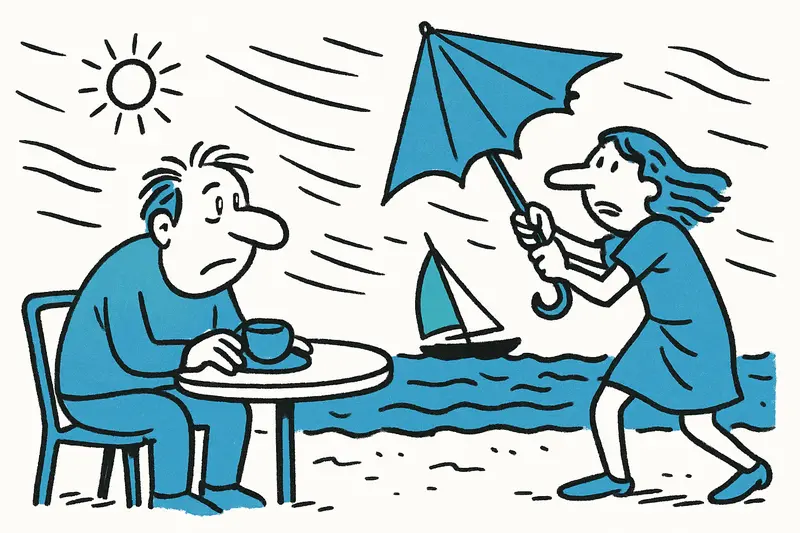

The regional government reported at the end of August: water reserves in the Balearic Islands are down to only 41 percent. This is more than a number on paper — it is the quiet dripping on the house walls, the early-morning hum of cicadas over dusty fields, and the pragmatic optimism at the beach bar when the tap runs a bit leaner. One central question remains: how long will the water last if the summer stays this dry and warm? Other coverage places storage volumes slightly higher and discusses regional nuance in 44% and Still Uneasy: Why Mallorca's Water Situation Remains Regionally Critical.

Where it is most urgent

The distribution shows that not all islands are affected equally: Menorca is at around 34 percent, Ibiza even at only about 27 percent. Mallorca falls between these values according to the government, but with strong regional differences, as reported in When the reservoirs shrink: How Mallorca's water shortage affects Palma and the villages. The Spanish weather service AEMET confirms: August was unusually warm and largely dry. Mallorca saw only about 13 liters per square meter, Ibiza barely more than 1 liter — that does not fill reservoirs or cisterns.

More than the daily drop: consequences for everyday life and the economy

Drinking water has priority — and rightly so. But the tightened tap affects vegetable gardens, small farms in Campos and Santanyí, and the subtle logistics of hotels: irrigation times are shifted, mobile water supplies stand ready as emergency measures, and at Platja de Palma neighbours now mostly water early mornings and late evenings to avoid evaporation. Those who work professionally with water — gardeners, farmers, hotel technicians — feel the shortage first.

What is often missing from the public debate is the social distribution: small-scale farmers across Mallorca have less room to manoeuvre than large agricultural companies or hotels that can rely on private wells or expensive deliveries. That creates inequality in a crisis that affects everyone.

The long-term questions: too expensive, too slow — or simply necessary?

Politically, seawater desalination, better networks and subsidy programs for water-saving technology are being discussed again. These are the right approaches — but they have drawbacks. Desalination plants require a lot of energy and drive up costs; as the IEA desalination report explains, they can worsen the climate footprint if the electricity supply is not clean. The same applies to large-scale infrastructure projects: they are expensive and take years. The key questions therefore are: who pays, and how quickly can measures actually take effect?

Another point that is rarely spoken out loud: the islands have been drawing water from groundwater aquifers for decades, some of which are overexploited. This leads to salinization and a long-term loss of fresh groundwater — a problem that cannot be solved by expensive desalination plants alone. Local reporting on shrinking reservoirs and the pressure on Palma is detailed in Water shortage in Mallorca: As Gorg Blau and Cúber shrink — is Palma really prepared?. A sustainable plan would therefore need to include water retention, rainwater cisterns, reuse of greywater and treated wastewater for agriculture, and consistent management of existing network losses.

Concrete, feasible steps — immediate and mid-term

What will really help in the coming months is not a single miracle solution but a bundle of quick and mid-term measures:

- Leak detection and repair: many networks lose 20–30 percent of water to leaks. Quick fixes save a lot and make economic sense.

- Subsidy programs for drip irrigation and moisture sensors: small farmers need incentives, not just rules.

- Large-scale rain retention projects and municipal cisterns: rain is scarce, but every drop counts.

- Targeted expansion of desalination capacity coupled with renewable energy: if desalination is used, make it as climate-friendly as possible.

- Reuse at municipal level: treated wastewater for parks and agriculture eases the demand on drinking water supplies.

- Transparent and fair prioritization: who gets water during droughts — hotels, agriculture, households? This must be discussed publicly.

Looking ahead: local responsibility

Autumn brings meteorological uncertainty — AEMET sees seasonal fluctuations but no clear turnaround. In the short term, saving remains the most effective measure: less car washing, targeted watering during the cool hours, and timely repairs of water pipes. Locally this also means: mayors, municipal councils, farmers and hoteliers must plan together now. In the streets, at the market in Inca or at the harbour of Portocolom you hear the same message: "Waste less, plan better."

A personal impression: At the baker's on the corner in Son Servera people now ask more often how to save water at home. It is a small, almost everyday dialogue — but such conversations are the start of collective adaptation. If the islands invest wisely and act in solidarity, the crisis can be mitigated. Ignoring it is not an option.

Similar News

Burger Week and Restaurant Week: How February Comes to Life on Mallorca

Sixteen venues compete for bites and likes: the Fan Burger Week (Feb 16–22) entices with special offers and a raffle to ...

Cause inflammation on contact: How dangerous are the processionary caterpillars in Mallorca — and what needs to change now?

The caterpillars of the processionary moth are currently causing trouble in pine forests and parks. Authorities are remo...

Teenager seriously injured on Ma-2110: Why this night road needs more protection

A 17-year-old was seriously injured on the Ma-2110 between Inca and Lloseta. A night road, lack of visibility and missin...

Storm warning again despite spring sunshine: what Mallorca's coasts need to know now

Sunny days, 20+ °C – and yet the warning system beeps. AEMET reports a yellow storm warning for the night into Tuesday f...

Final installment for the Palma Arena: a small weight lifts from the Balearics

The Velòdrom Illes Balears will pay the final installment of its large construction loan on July 13, 2026. For Mallorca ...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca