Why the Balearic Islands Report Spain's Lowest Absenteeism Rate — and What Downsides That May Hide

The Balearic Islands have the lowest absenteeism rate in Spain at 5.6 percent. Sounds good — but behind the figures are seasonal effects, precarious employment and a risk: suppressed sickness absence instead of genuine health. What employers and policymakers should do now.

Fewer absences — blessing or misconception for the islands?

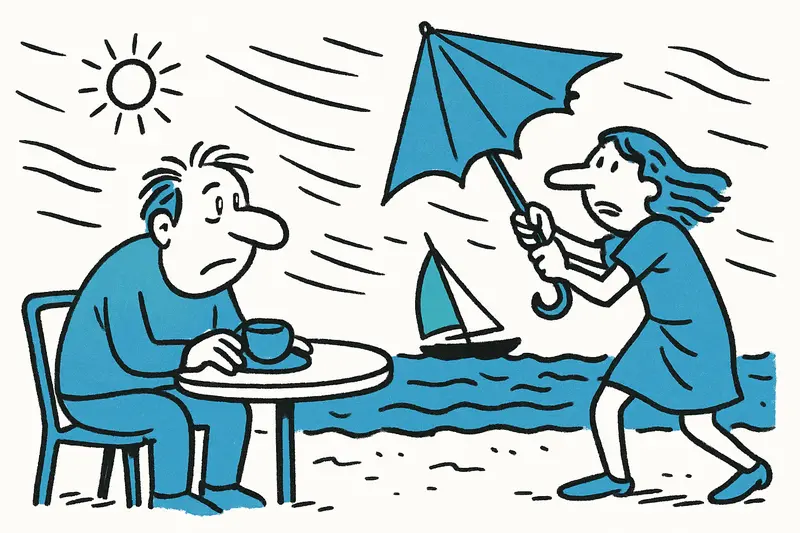

Strolling through Palma in the morning, you hear the clatter of cups on the Plaça de Cort, the rattle of mopeds and see hotel staff arriving promptly for their shifts. A recent analysis shows: in the first quarter the Balearic Islands had an absenteeism rate of only 5.6 percent absenteeism rate in the Balearic Islands — well below the Spanish average of seven percent. At first glance this looks like a positive signal for employers and the local economy. But statistics are only one side of the coin.

The central question is: does a low figure really mean employees are better off here — or does it simply reveal structural peculiarities of the labor market? A few details are worth a closer look.

What pulls the numbers down — and what distorts them

The Balearic economy is dominated by services. Hotels, gastronomy, retail and tourism shape everyday life. Many jobs are local, commutes are short. That reduces short-term absences: shorter journeys, closer collegial ties, neighbors helping out when someone is absent. Remote work in administrative roles and the mild climate also play a part. For sick leave specifically the rate was even lower at 4.4 percent medically certified sick leave, while the Canary Islands recorded around 7.6 percent.

But there are factors that are often underreported in public debate: seasonal contracts and temporary employment statistics, informal employment and a culture of "powering through." Presenteeism distorts the statistics — short-term workers are absent in different ways, and employers sometimes report absences less rigorously. Not every absence is officially recorded; in some businesses the risk of losing a job is real. This can lead to employees coming to work sick — presenteeism instead of legitimate absence.

Moreover, the figure lags behind other problems: mental strain during peak season, physical exhaustion among service workers and construction crews, and language barriers in international teams. These are aspects that simple absenteeism rates do not capture.

What companies and policymakers can do concretely

It is not enough to rely on a good number. This result points to clear fields of action: better contract forms, preventive health services and more flexible working time models. Concrete measures could include:

1. More reliable health programs: regular check-ups, vaccination campaigns in hotels and free health advice for seasonal workers — close to the workplace, in the evenings after shifts.

2. More flexible shift plans: shorter shifts at peak times, shift-exchange platforms within companies and emergency funds for short-term replacements.

3. Better contract and reporting practices: promotion of longer-term contracts, clear reporting systems for sick leave and protections for employees who need to be absent — so absences are not concealed out of fear.

4. Take mental health seriously: training for managers, anonymous counseling services and more rest areas in hotels and on construction sites: some problems cannot be solved with a band-aid.

A look ahead — opportunities instead of complacency

The Balearic Islands can use the low level of absenteeism in the Balearic Islands as a quality feature of the labor market. If employers take the statistic seriously and invest in sustainable working conditions, everyone benefits: more stable teams, better planning and less staff turnover. But if the figure is merely cited to justify cuts or loosen controls, working conditions may deteriorate.

In the end, a sober finding remains: the islands perform well in this statistic — but good numbers are no substitute for good work. At the next espresso on the Rambla it is worth asking the server: do they come to work because they can — or because they have to? That not only warms the heart briefly but also shows where we as an island community should make improvements.

Note: The measures suggested here are pragmatic approaches drawn from everyday experience from Palma to Calvià. They require political support and the willingness of employers to really take effect.

Similar News

Burger Week and Restaurant Week: How February Comes to Life on Mallorca

Sixteen venues compete for bites and likes: the Fan Burger Week (Feb 16–22) entices with special offers and a raffle to ...

Cause inflammation on contact: How dangerous are the processionary caterpillars in Mallorca — and what needs to change now?

The caterpillars of the processionary moth are currently causing trouble in pine forests and parks. Authorities are remo...

Teenager seriously injured on Ma-2110: Why this night road needs more protection

A 17-year-old was seriously injured on the Ma-2110 between Inca and Lloseta. A night road, lack of visibility and missin...

Storm warning again despite spring sunshine: what Mallorca's coasts need to know now

Sunny days, 20+ °C – and yet the warning system beeps. AEMET reports a yellow storm warning for the night into Tuesday f...

Final installment for the Palma Arena: a small weight lifts from the Balearics

The Velòdrom Illes Balears will pay the final installment of its large construction loan on July 13, 2026. For Mallorca ...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca