Population Decline in the Balearic Islands: Small Minus, Big Questions

Population Decline in the Balearic Islands: Small Minus, Big Questions

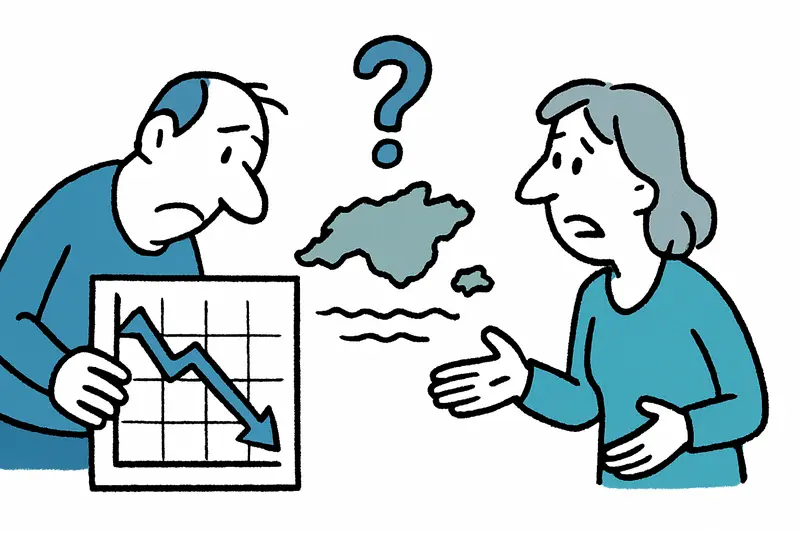

For the first time in years the Balearic Islands shrank in the quarter — 0.07 percent fewer inhabitants. Why the signal matters more than the number and what Mallorca specifically lacks.

Population decline in the Balearic Islands: small decrease, big questions

0.07 percent in a quarter — a statistical blip or a wake-up call for the islands?

The latest figures from Spain's National Statistics Institute (INE) reveal a surprising detail: in the last quarter the population of the Balearic Islands fell by 0.07 percent. On an annual basis, however, more people still live here than a year ago — around 1.26 million, roughly 9,700 more people, mostly immigrants from abroad, especially from Colombia and Morocco, as noted in Population boom in the Balearic Islands: What does it mean for Mallorca?.

Key question: Does a marginal quarterly decrease say anything about the islands' long-term development — and if so, what exactly?

Critical analysis: A decline of 0.07 percent may at first sound like measurement noise. But quarterly figures are windows that can signal trends early. For example, Have the Balearic Islands really become less crowded? A look at the August 2025 numbers examines short-term changes in visitor density. On the Balearic Islands several forces overlap: seasonal work, tourism-driven rental markets, an aging population in many villages, and sustained demand for workers in construction and services. If immigration continues to be the main driver of population growth, the islands remain vulnerable to economic fluctuations and political changes in the countries of origin.

What is missing from public discourse: Most conversations focus on tourist numbers and hotel beds; the tension between statistics and everyday scenes is explored in Balearic Islands on average quieter — Palma stays full: Why statistics and everyday life contradict each other. Less attention is paid to internal migration within Spain, the role of long-term holiday residents, the conversion of homes into tourist apartments, and the seasonal fluctuation of municipal registrations. Nor is there sufficient discussion about how the age structure changes in individual municipalities: Palma is growing, rural places are aging and losing inhabitants — with consequences for schools, healthcare and bus services, as detailed in Who Shapes Mallorca's Streets? A Reality Check on Island Demographics.

Everyday scene: Early in the morning on Palma's Paseo Marítimo you hear vans unloading fish from the harbor and retirees leafing through their newspapers. In a small café on the Plaça Mayor a young caregiver from Colombia orders her café con leche before going to work at a nursing home. On the way, neighbors at the market talk about high rents — a theme that repeatedly pushes families to move to the mainland. Such scenes show: demographic numbers are not an abstraction but everyday life, noise and housing problems.

Concrete solutions: 1) Better, more timely measurement of the seasonal population — municipalities should more clearly record short-term rentals and second homes. 2) More social housing and incentives for long-term rental contracts so workers do not have to move every season. 3) Integration initiatives: targeted language and vocational courses for newcomers from countries like Colombia and Morocco, linked to recognition procedures for qualifications. 4) Regional labor-market policies: cooperation between municipalities, tourism businesses and training institutions to retain skilled workers locally. 5) Support programs for young families in inland areas — improve infrastructure and digital connectivity so regions remain viable.

Politics and administration cannot just wait for national figures. Short-term signals like a small quarterly decline should be a reason to look more closely: Where are we losing people — in which age groups, in which municipalities — and why? A more differentiated data situation helps make measures more targeted.

Concise conclusion: The Balearic Islands are not on the brink, but they stand at a crossroads. A 0.07 percent drop is not a drama, yet it is a reminder that growth driven almost entirely by foreigners is fragile. Anyone who wants the islands to remain socially and economically stable must start now to organize housing, work and integration so that people stay longer — not only for the season.

Read, researched, and newly interpreted for you: Source

Similar News

Porreres: How Neutering and Volunteers Change Cats' Lives

In Porreres a veterinarian and volunteers show how targeted neutering, microchipping and municipal support stabilize cat...

New Photos from the Crown Prince Family's Mallorca Holiday: Closeness Instead of Showing Off

The Spanish Casa Real released previously unpublished shots from the summers of 2012 and 2013: Felipe, Letizia and their...

When a Housing Shortage Fills the Coffers: Record Revenues in the Balearic Islands and the Islands' Bill

In 2025 the Balearic Islands recorded for the first time more than €6 billion in tax revenue — driven mainly by high pro...

Arrest after fires in S'Albufera: A reality check for prevention and protection

A 72-year-old man was arrested in S'Albufera. Why repeated fires were possible, which gaps remain, and what must happen ...

Electronic 'Co‑Pilot' for Mallorca's Trains – More Safety, but Which Questions Remain?

The Balearic government announces ERTMS for the island: pilot in 2026, metro 2027, rail network 2028–2029. A look at opp...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca