Who Shapes Mallorca's Streets? A Reality Check on Island Demographics

Who Shapes Mallorca's Streets? A Reality Check on Island Demographics

The Balearic Islands are approaching a turning point: in a few years, those born on the islands could become a minority. What does that mean for the urban landscape, language and everyday life — and which answers are still missing?

Who Shapes Mallorca's Streets? A Reality Check on Island Demographics

A minority in two years? Numbers, everyday scenes and what should be done now

On the Passeig del Born in Palma I hear Spanish, Catalan, English and sometimes Rumor del Caribe from a café window in the morning. Construction noise mixes with the smell of freshly brewed café con leche. The fact that the voices on the corner sound increasingly mixed is not just my impression: current data show that only just over half of the Balearic residents were born in the region, and that share is continuing to fall, as reported in Population boom in the Balearic Islands: What does it mean for Mallorca?.

Briefly the bare numbers, without alarmism: around 51.5 percent of people in the Balearics were born in the region; the share of locally born residents is declining. At the same time, almost 29 percent of the islanders hold a foreign nationality. Foreign nationals therefore form a larger group than people who moved here from mainland Spain, who make up only about 20 percent of the population. In recent years the number of foreigners increased by well over 60,000 people; growth came particularly from Latin American countries and from Morocco, as explored in How many residents can Mallorca sustain? Growth, pressure and ways out of overcrowding. Within Mallorca the proportions vary greatly: in Calvià only around 37 percent were born in the archipelago, while in Mancor de la Vall about 78 percent were. Formentera and Ibiza show the strongest mixing.

What does this mean in concrete terms? First: multilingualism is no longer the exception but the everyday reality. At the market in Sant Antoni or in the bay of Port d’Alcúdia you meet sellers, craftsmen and parents with prams who have a different origin than their neighbors. This changes culture, gastronomy and the urban landscape: different shops, different offerings, new religious and cultural meeting places. This is vibrant, but it also raises questions: who has access to affordable housing? Which languages are prioritized in authorities, schools and clinics? And how can local politics remain accessible when election results look different than before?

Official interpretations name two main factors: an almost zero natural population growth — hardly any children are being born — and high living costs, especially housing. Many people who once moved here from the mainland leave the islands again, often after retirement, because life on the mainland is significantly cheaper. The result: fewer locally born residents, immigration from abroad and a net outflow of mainland Spaniards. The drop in newborns is documented in Birth Crisis in the Balearic Islands: What Does the Decline Mean for Mallorca?.

What is missing in the public discourse: firstly the role of labor market structures and part-time employment that prevent young families from staying. Secondly, the effects of second homes and short-term rentals on rental prices in villages and cities. Thirdly, clear local integration strategies are often lacking that go beyond language courses — for example recognition of professional qualifications, targeted job placement and childcare that gives young parents real freedom of choice.

Practical measures that seem feasible: a municipal program for affordable housing with rent caps for social groups; more daycare places and financial incentives for young families; targeted support for vocational qualifications so that newly arrived professionals can establish themselves; reducing bureaucracy in the recognition of foreign qualifications; and transparent data collection so municipalities can react in time. A serious regulation of short-term rentals, coupled with investment in social housing, would also relieve pressure on the housing market.

An everyday example: in a bakery in Sineu the baker speaks Mallorquí with a mother from Colombia whose children are already learning Catalan at school. Both benefit: the baker sells new flavors, the mother finds social connections. Such neighborhoods can be a model if the framework conditions are right — affordable rents, daycare places and supportive school offerings.

Final note: the demographic shift is not a natural event that one merely records. It is the result of decisions — in the housing market, tax policy, urban planning and family policy. Those who now only lament the changing streetscape overlook the causes: structural problems that drive people away or attract them. Solutions can be found if municipalities set clear priorities: secure housing, organize integration practically, and relieve families. Otherwise the face of the island will change without island society having a say in how it changes.

Read, researched, and newly interpreted for you: Source

Similar News

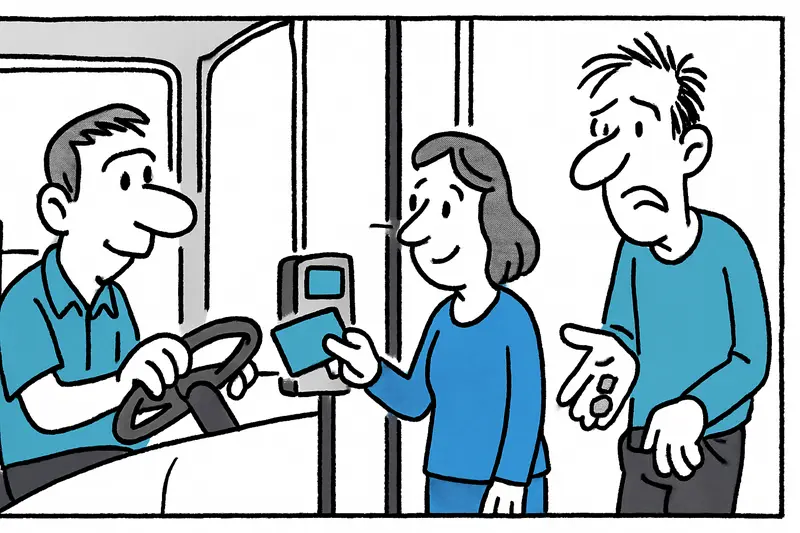

Card payments on Palma's city buses – relief or nuisance?

EMT is rolling out card readers in Palma's buses: about 134 vehicles already equipped, group discount rules — but also t...

Knee-high water at Playa de Palma: What to do about the recurring floods?

Torrential rainfall flooded the Playa de Palma, with walkways knee-deep in water. An assessment of what's missing and ho...

Llucmajor gets beaches ready: new signs, pruned palms and preparations for the summer season

Llucmajor is preparing for the bathing season: palms in s'Arenal have been trimmed, 16 bathing areas will receive inform...

Mallorca Between Pragmatism and Panic: What Will Spain's Mass Regularization Bring?

Madrid plans an extraordinary regularization for up to 800,000 people. On Mallorca, concerns about capacity clash with e...

When the rain front "Kristin" hit: A reality check for Mallorca

Midday showers turned streets into brown torrents and triggered an orange alert. A critical look at preparedness, commun...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca