Island council wants to contain the blue crab — is the new package of measures enough?

Island council wants to contain the blue crab — is the new package of measures enough?

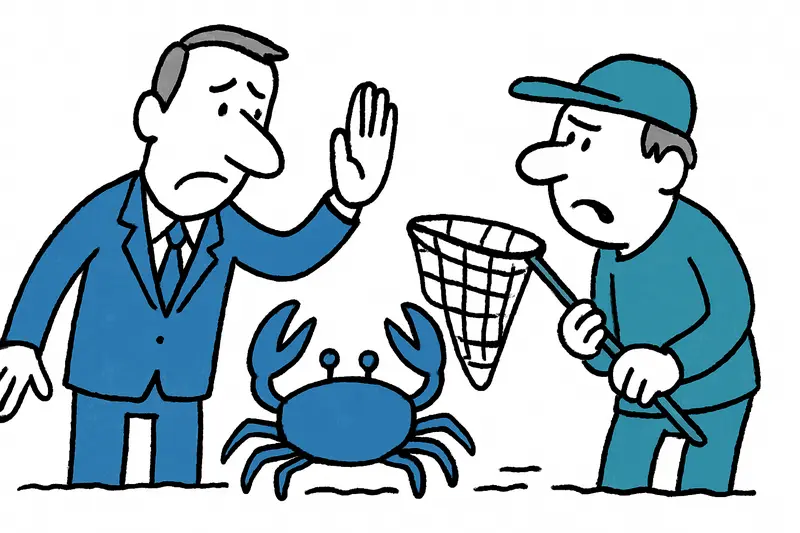

The Consell will now allow the catching of the invasive blue crab in almost all waters of Mallorca and deploy more fishing gear. A reality check: what's missing, what could go wrong — and what really helps?

Island council wants to contain the blue crab — is the new package of measures enough?

Key question: Can expanding fishing rights and allowing additional gear alone solve the ecological problem?

From 2026 to 2030, recreational anglers will be allowed by decision of the island council Mallorca Magic article 'El Consell quiere frenar al cangrejo azul — ¿es suficiente el nuevo paquete de medidas?' to catch the so‑called blue crab in almost all waters of Mallorca; only protected areas are to be excluded. In addition, fishing rods, landing nets and grabbers will be officially permitted. Since 2020, hobby anglers have reportedly removed around 15,000 animals from the water, according to the Consell. That sounds like practical action — but the answer to the key question is more complicated.

First critical observation: More permitted gear means more activity on harbour moles, in small bays like Portixol or Cala Major and along the rocky shores of the north coast. In the mornings, when the ferries are still running and gulls circle overhead, you already increasingly see buckets, nets and rubber gloves. That's good — but it doesn't automatically suffice. The official expansion of allowed methods is detailed in local coverage Mallorca Magic coverage 'El consejo insular endurece las reglas contra el cangrejo azul – ¿es suficiente?', which notes the broader list of permitted gear.

Ecologically, the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) is an opportunist. It reproduces quickly, eats juvenile fish and mussels, and can shift existing food webs. Fishing pressure from amateur anglers can provide local relief, but without a coordinated strategy gaps easily arise: fishing areas are used unevenly, nursery zones remain untouched, and bycatch of protected species through improper methods is a real risk.

Another problem is data. The figure of around 15,000 caught animals sounds impressive — but the number says little about population trends, catch locations, seasonal patterns or the size of the animals. Without systematic recording, it remains unclear whether the population is declining or merely shifting locally. This sober data perspective is often missing from public debate; local reporting and analysis such as Mallorca Magic report 'Problema del cangrejo azul: por qué la resolución del Consejo Insular debe ser solo el comienzo' highlight the need for better records.

Control and enforcement are the second construction site. If fishing is allowed almost everywhere, clear rules are needed for the disposal of caught animals, minimum sizes and reporting obligations. Otherwise, dead crabs end up in backyards or the trash, and the effort fizzles out. So far, the Consell has not named comprehensive reporting channels that are also low‑threshold for recreational anglers.

What else is missing in the debate? Social incentives. Many anglers act voluntarily, out of interest or frustration at the visible impact of the species. But if the commitment is not publicly acknowledged and not accompanied by simple instructions, willingness declines. In conversations at the harbour of Sóller you often hear: 'I'd gladly help, but how do I do it correctly?'

Concrete approaches that could help sustainably are not rocket science — but they must be combined. First: systematic catch and reporting registers. A simple online form, a WhatsApp hotline or an app can record location data, catch numbers and sizes. Second: training at harbours and through angling clubs — short workshops on proper handling, avoiding bycatch and safe disposal. Third: targeted removal actions in hotspots, accompanied by scientists from the University of the Balearic Islands (UIB) or by marine biologists to validate the data.

Furthermore, rules on fishing gear should be more sensible: grabbers and landing nets are useful, but traps and pots need size and mesh specifications to protect juveniles and non‑target species. A time‑limited but controlled 'catch zone' with additional monitoring could show whether increased pressure actually reduces the population.

A pragmatic point: utilization. In markets or restaurants, invasive species must not automatically be marketed — that can create new commercial links. On the other hand, controlled use (e.g. local initiatives to process the catch into animal feed or compost, if hygiene standards allow) can create incentives for more fishing without fueling a market.

Where public transparency is lacking, acceptance is lacking. The Consell should accompany the measures with clear reports, maps of catch sites and success indicators. Then the neighbours on the promenade in Portixol or the boat owners in Port de Sóller will know that their efforts are not merely symbolic.

Everyday scene: a Saturday morning on the mole — older men with coffee cups, two tourists looking at a crab in a bucket, children asking questions. These are moments to be used: set up 'participation stations' on weekends where volunteers count crabs and briefly clean them under guidance. This creates knowledge and, above all, trust.

Conclusion: The extended catching rights are a step in the right direction, but not a cure‑all. Without data systems, clear disposal routes, training, monitoring and careful regulation, unwanted side effects threaten — and the blue crab will remain. The island council has granted the permission; now the work remains to implement it smartly and practically. Those who stand by the water in the morning feel it: people want to help. Now structures are needed so that helping actually has an effect.

Concrete next steps, briefly: 1) set up reporting and data systems; 2) training and information stands at harbours; 3) hotspot controls with scientific supervision; 4) clear rules on traps and minimum sizes; 5) transparent success measurement and communication.

Read, researched, and newly interpreted for you: Source

Similar News

27 years, a 'Yes' and the island as witness: Peggy Jerofke and Steff Jerkel celebrate on Majorca

After a long period of ups and downs, Peggy Jerofke and Steff Jerkel plan to marry on June 26 in the east of Majorca. A ...

Jan Hofer on Mallorca: Homesick for Wholegrain — Yet Settled

The 75-year-old TV veteran lives on the island with his wife, takes small homeland trips to Can Pastilla and sometimes m...

Card payments on Palma's city buses – relief or nuisance?

EMT is rolling out card readers in Palma's buses: about 134 vehicles already equipped, group discount rules — but also t...

Knee-high water at Playa de Palma: What to do about the recurring floods?

Torrential rainfall flooded the Playa de Palma, with walkways knee-deep in water. An assessment of what's missing and ho...

Llucmajor gets beaches ready: new signs, pruned palms and preparations for the summer season

Llucmajor is preparing for the bathing season: palms in s'Arenal have been trimmed, 16 bathing areas will receive inform...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca