Royal Memoirs and Mallorca: Between Anecdote and Reality

Royal Memoirs and Mallorca: Between Anecdote and Reality

In his memoirs Juan Carlos I. portrayed Mallorca as a stage — an image full of sailing yachts, state guests and family memories. But how much influence did the Crown really have on the island's development?

Royal Memoirs and Mallorca: Between Anecdote and Reality

That the new memoirs of Juan Carlos I biography at Britannica, titled Reconciliación and written together with Laurence Debray, give Mallorca considerable space is no coincidence. The former king describes how, since the 1960s, he invited guests from around the world to the Marivent Palace Wikipedia page — from sailing trips with heads of state to the summer receptions he presents as contributing to Palma's international profile.

Key question

The question that arises: Do such memories form a reliable history of the island, or are they primarily a personal testimony — an attempt to affirm influence and significance from a personal perspective?

The accounts contain concrete data points: first participation in a regatta in 1969, regular summers at Marivent from 1974, the house between Palma and Cala Major, built in the 1920s by architect Juan de Saridakis. He mentions big names, sailing trips on the Fortuna and also darker chapters — a defused bomb in 1977 and a failed assassination attempt in the 1990s near the harbor. After his abdication in 2014 he is said to have completely withdrawn from the island, with only a brief appearance in 2018; since then he has preferred other places for official visits.

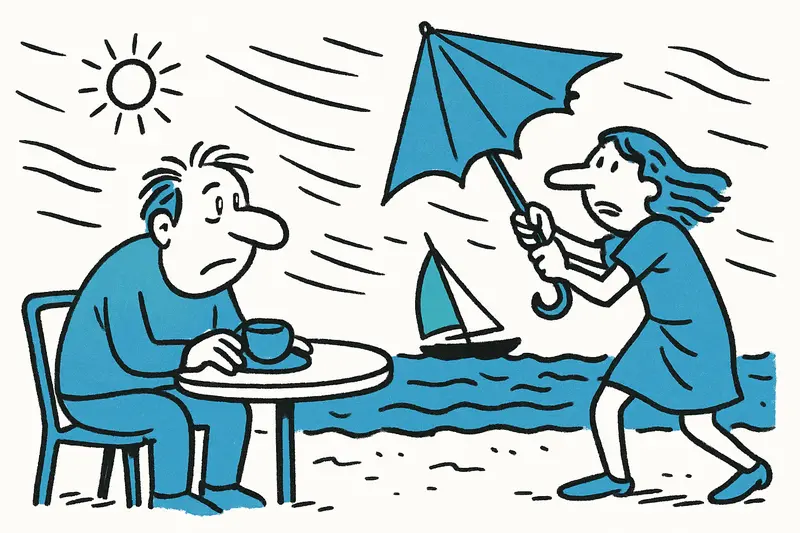

Those who know the daily reality here in Mallorca — the fishermen at Portixol, the morning buoy setters on the Passeig Marítim de Palma Wikipedia page, the cafés at Moll Vell — feel immediately: the island was never just the stage of a single person. Palma's rise to an international travel destination is the result of many factors: better flight connections, changed holiday patterns in Europe, the commitment of local hoteliers and entrepreneurs, the development of harbors and regatta infrastructure, as well as a long series of cultural and economic decisions by the municipalities.

The book makes no claims, nor does it deny anything. Nevertheless, it remains open how much royal receptions actually influenced structural development. A state guest aboard a yacht makes headlines, yes — but do they create airports, roads, or jobs? This distinction is part of what is often missing in public discourse.

Another question mark: the perspective of the locals. In the memoirs private memories are prominent, while voices from the neighborhood of Cala Major, dockworkers, entrepreneurs and sailing clubs are largely missing. This is not only literarily relevant but political: memory politics shapes which aspects of a story become visible.

An everyday scene helps to locate this: on a cool December morning, when the boats on the Passeig are still swinging on chains and the trash collectors push their carts, people talk less about royal anecdotes than about rent prices, parking spaces and the specific dates of the Copa del Rey regatta Wikipedia page. The regatta is more tangible for many here than any royal anecdote — it brings work for sailmakers, the hospitality sector and skippers, not just photos for the gossip columns.

What is missing in public discussion? First: empirical data on the economic effect of royal visits. Second: local voices that explain how Marivent and the yachting industry actually impact the community — positively or burdensome. Third: transparency regarding historical security issues; mentioning is good, investigation and archival work are better.

Concrete approaches to complete the picture: a municipal collection of oral histories — interviews with dockworkers, club members and entrepreneurs who have accompanied regattas and reception operations. The city council could digitize files from the relevant decades and make them more easily accessible. For the regattas it would be conceivable to create accompanying educational offerings — cheaper tickets for residents, workshops in schools about maritime professions, open harbor tours during regatta phases.

The royal family also has options to support the narrative shift: more engagement with local heritage, less secluded receptions, more visible support for smaller, charitable projects on site. That would not disprove the memoirs, but it would complete the picture.

Conclusion: the autobiography of a ruler remains, above all, personal. It can preserve memories and spark debates. But it is no substitute for documented local history. Anyone who sees the lights along the Passeig Marítim in Palma in the evening knows: Mallorca is a complex web of people, businesses and memories — royal sailing was only one of many threads. If we seriously want to know how the island became what it is, then we need more voices than a chapter in a book.

Read, researched, and newly interpreted for you: Source

Similar News

Burger Week and Restaurant Week: How February Comes to Life on Mallorca

Sixteen venues compete for bites and likes: the Fan Burger Week (Feb 16–22) entices with special offers and a raffle to ...

Cause inflammation on contact: How dangerous are the processionary caterpillars in Mallorca — and what needs to change now?

The caterpillars of the processionary moth are currently causing trouble in pine forests and parks. Authorities are remo...

Teenager seriously injured on Ma-2110: Why this night road needs more protection

A 17-year-old was seriously injured on the Ma-2110 between Inca and Lloseta. A night road, lack of visibility and missin...

Storm warning again despite spring sunshine: what Mallorca's coasts need to know now

Sunny days, 20+ °C – and yet the warning system beeps. AEMET reports a yellow storm warning for the night into Tuesday f...

Final installment for the Palma Arena: a small weight lifts from the Balearics

The Velòdrom Illes Balears will pay the final installment of its large construction loan on July 13, 2026. For Mallorca ...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca