"In Germany I was often alone": Why Sali swapped Düsseldorf for Mallorca

Sali worked in Poland, drove trucks in Düsseldorf and now spends the season in Mallorca — juggling three jobs, a room with a sea view and a diverse circle of friends. He explains from El Arenal why he prefers to stay here despite hard work.

From the factory hall over the highway to the promenade: a modern commute

I meet Sali on a Monday morning in El Arenal, right by the harbor. The seagulls cry, somewhere a bratwurst sizzles at a snack stand, and the harbor wind carries the smell of salt water and engine oil. The 37-year-old laughs a lot, speaks quickly and switches between Arabic, Polish, Spanish, some German and a touch of English. His route across Europe reads like the short version of a new migrant labor pattern: factory work in Poland, a year of truck driving in Düsseldorf, and now the season in Mallorca with three jobs at once — kitchen, service, beach work.

Poland: hard work, real friendships

In Poland he worked in a factory. "Hard, yes. But I had friends," Sali says, shrugging. Saturdays at the market, beers with colleagues in the evenings, helping each other with paperwork — rituals that are more than leisure. He learned Polish so well that he sometimes even dreams in Polish. His account of Poland sounds warm, almost like a second home: social networks, shared breaks, a language that opened doors.

Düsseldorf: good money, little heart

Germany was different. "The pay was better — net around €1,600 — but I was often alone," he says. As a truck driver he drove long distances, the days were regimented, the evenings empty. Politeness met distance: ticket checks, fines, the feeling of constantly having to be explained. Despite language skills, the role of the foreigner remained visible to many. For Sali that became exhausting, almost heavier than the physical work. He asked himself: Do I want to keep breathing here with this taste of foreignness?

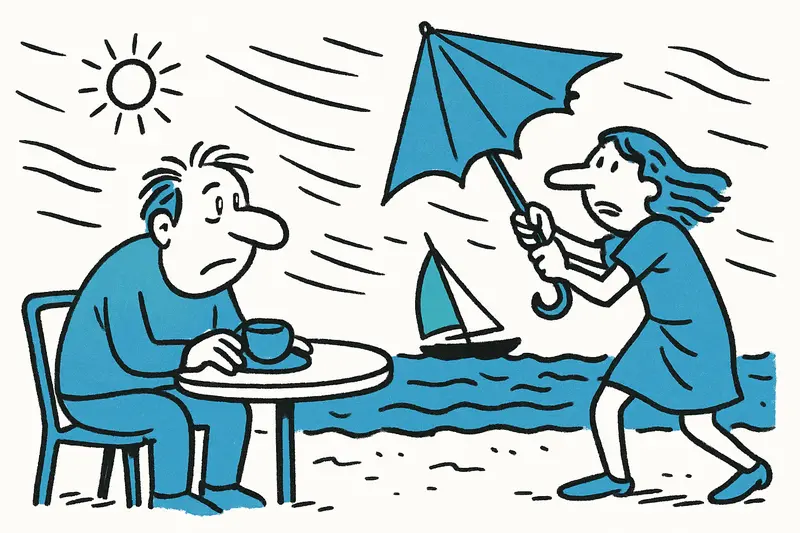

Mallorca: sun, shift schedules, social air to breathe

On the island many things are more improvised. The shifts are long, breaks short, the work physical. But there is something else: a relaxed way of interacting, a sense of "it's enough to be who you are". His landlord, a hotel manager, gave him a small room with a sea view at a price that feels fair to him. Evenings are communal — sangría, cooking together, carpooling to shifts. "Here I don't have to explain myself all the time," Sali says. In El Arenal he knows the short ways: the baker, the phone shop, the colleague who fixes the coffee machine in the morning. Social capital often counts more than higher pay.

Between precarity and protection: the uncomfortable question

But the sunny backdrop should not hide the fact that seasonal work remains precarious. Three jobs, uncertain hours, hardly any social insurance across the season — these are facts many overlook when they only see the postcard motifs, as discussed in When One Job Isn't Enough: Why People in Mallorca Often Work Multiple Shifts. Sali shuttles outside the season between Poland and Tunisia, sends money home and thus secures the year. Mallorca offers income and networks, but no guarantee of stability.

What is often missing in public debate

The conversation with Sali raises a guiding question: Why do people choose places like Mallorca despite difficult working conditions? The answers are complex: communal closeness, everyday language that is understandable, a landlord who provides a place to stay, fewer daily hostilities. The debate about "seasonal tourism" often stays with numbers — beds, revenue, amount of waste — a focus that echoes broader analyses such as Not Just Mallorca: Why So Many Germans Make Their Home Elsewhere. Less frequently discussed is the social infrastructure of those who keep the island running: housing conditions, advice for migrants, access to health and support services, recognition of qualifications.

Concrete: opportunities and solutions

A few ideas are obvious and comparatively easy to implement, but could have impact: stronger checks on seasonal work contracts, transparency about hours and social contributions, binding minimum standards for arranged accommodation, low-threshold advice centers at tourist hubs, more services in multiple languages — from health checks to psychological counseling. Local initiatives that promote exchange between seasonal workers and longer-term residents can also help stabilize a sense of belonging.

A personal conclusion: For Sali it's not just about money. It's about living in a place where you don't constantly have to explain your background, where you can laugh after a shift and come back the next morning. Mallorca is not a secure endpoint for him right now, more a breathing space with a sea view — and that matters to many more than bare numbers suggest.

Similar News

Burger Week and Restaurant Week: How February Comes to Life on Mallorca

Sixteen venues compete for bites and likes: the Fan Burger Week (Feb 16–22) entices with special offers and a raffle to ...

Cause inflammation on contact: How dangerous are the processionary caterpillars in Mallorca — and what needs to change now?

The caterpillars of the processionary moth are currently causing trouble in pine forests and parks. Authorities are remo...

Teenager seriously injured on Ma-2110: Why this night road needs more protection

A 17-year-old was seriously injured on the Ma-2110 between Inca and Lloseta. A night road, lack of visibility and missin...

Storm warning again despite spring sunshine: what Mallorca's coasts need to know now

Sunny days, 20+ °C – and yet the warning system beeps. AEMET reports a yellow storm warning for the night into Tuesday f...

Final installment for the Palma Arena: a small weight lifts from the Balearics

The Velòdrom Illes Balears will pay the final installment of its large construction loan on July 13, 2026. For Mallorca ...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca