'A snake eats another' - what cannibalism among invasive snakes reveals about Mallorca's ecosystem

'A snake eats another' - what cannibalism among invasive snakes reveals about Mallorca's ecosystem

A first documented observation: an adult Garrigue snake (Macroprotodon mauritanicus) swallows a juvenile horseshoe whip snake (Hemorrhois hippocrepis). What looks like a macabre nature photo is a warning sign for Mallorca's ecology - and exposes gaps in prevention and monitoring.

'A snake eats another' - what cannibalism among invasive snakes reveals about Mallorca's ecosystem

First documented observation in the Balearics raises uncomfortable questions

Key question: What does a documented scene in which an adult Macroprotodon mauritanicus swallows a juvenile Hemorrhois hippocrepis say about the situation on Mallorca - and what needs to change?

The incident is not a horror film but a scientifically described observation in the journal Acta Herpetologica, supported by the Institut Biodibal. An adult individual of the so-called Garrigue snake reportedly ate a juvenile horseshoe whip snake. This is the first documented interaction of this kind in the Balearics. At first glance an extraordinary anecdote, on closer inspection it is a symptom of a deeper problem.

Critical analysis: In recent years invasive snake populations have been spreading across Mallorca, as reported in Why Snakes Are Appearing More Often in Mallorca Now — Danger, Causes and What We Should Do. According to available information, many individuals apparently arrived on the island inside hollow olive trunks transported from the coast. This explains why the finca road between olive groves and Sunday markets is a hotspot: tree stumps and old woodpiles provide hiding places, and the transport of live plants creates pathways for introductions, as reported in Alarm at the Malgrats: Invasive Snakes Threaten the Sargantana. Is that alone enough to explain cannibalism? Not directly. Rather, the event points to altered predator-prey dynamics: when several non-native species meet in close proximity, competition, food availability and reproductive success change - animals react to that, sometimes brutally.

What is missing in the public debate: the story has been told as a curiosity, but rarely as a consequence of failures in prevention and controls. There is a lack of clear debate about plant imports, inspections in nurseries and the responsibility of traders and farmers. There is also little discussion about how landowners and municipalities can be systematically supported to recognize and deal with hollow trunks without promoting herbicide use or unnecessary clearances.

An everyday scene: early in the morning at the Inca weekly market, sellers unpack their olive oil cans and the smell of freshly fried ensaimadas fills the air, while the rattling of small trucks can be heard on the cobbles. An old farmer who has harvested olives for decades counts the trunks and quietly asks whether he should remove the hollow acacia by the roadside. He has seen snakes before, most recently in the summer 'more than ever'. Such observations are valuable but rarely recorded systematically.

Concrete solutions: First: an import register and stricter quarantine for larger plant shipments, especially for hollow trunks such as old olive trees, a measure discussed in Emergency in Mallorca: Why Olive Trees Are Suddenly Banned — and Whether That's Enough. This does not have to be an immediate blanket ban, but visual inspections and, where appropriate, heat treatment or fumigation should be considered. Second: a simple reporting-and-reward system for farmers and gardeners who report vulnerable sites - together with free guidance on safe removal of deadwood and proper storage. Third: expand monitoring through cooperation between Biodibal, universities and municipalities; regular mappings could quickly identify hotspots. Fourth: training for municipal workers and nurseries so invasives are detected already during loading. Fifth: public outreach with clear, practical advice (not panic guides, but: what to do when you spot a snake, how to photograph it, who to inform).

Practically this also means: fewer deadwood piles near houses, controlled removal of hollow trunks and targeted management at entry points. It costs money, but less than large-scale eradication programs once the problem gets out of control.

What could happen immediately: a temporary guideline from municipal administrations on handling hollow tree trunks and increased inspections in nurseries. Such measures can be implemented locally - at the finca, in the nursery, at the port. Experts like Biodibal are already involved; they need more staff and clear reporting channels to pool data.

Conclusion: the snake swallowing another is less a natural wonder than a warning sign. It shows how human trade routes and lack of precaution can change ecosystems. The image of an adult snake with a juvenile in its throat should not invite voyeurism but action: check better, report better, protect better. Otherwise the problems will keep eating their way through the island - and when solutions finally arrive, it may be too late.

Read, researched, and newly interpreted for you: Source

Similar News

Who pays for Palma Airport's ongoing construction chaos? A reality check

Aena plans €621.6M for 2027–2031 – almost 47% more than before. What island residents and travelers can actually expect ...

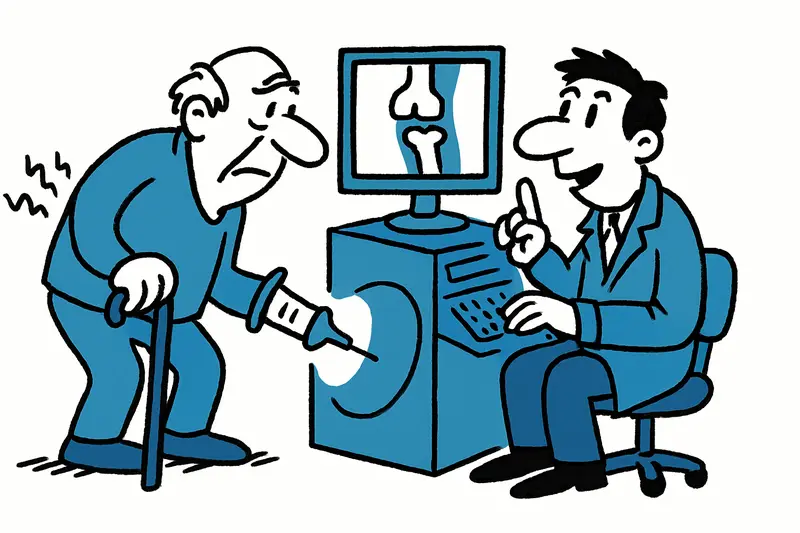

Regenerative Orthopedics in Nou Llevant: Modern Relief for Joint and Back Pain

New practice in Palma focuses on orthobiological procedures, shockwave therapy and the island's only whole-body cryocham...

Green without watering: Why artificial turf is becoming so popular in Mallorca

No mowing, no watering, always green: artificial turf creates well-kept outdoor spaces in Mallorca — from the terrace to...

Signature Retreats by Engel & Völkers: luxury with space and time on Mallorca

Engel & Völkers is bringing "Signature Retreats" — curated villas, concierge services and extended stays — to Mallorca. ...

Fischer Air and the Phantom Fleets: Why Mallorca Has Reason to Be Suspicious

Between announcements, investigations and allegedly stolen aircraft: why the promised Mallorca flights are questionable ...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca