62 Turtle Hatchlings in Palma – Night Watches, Protection and Uncomfortable Questions

At Can Pere Antoni, 62 loggerhead sea turtles hatched. Volunteers kept watch through the night — but do such actions really help in the long term? A look at protection measures, head-starting and the challenges of urban beaches.

62 turtle hatchlings emerge on Palma's city beach – a reason for joy and reflection

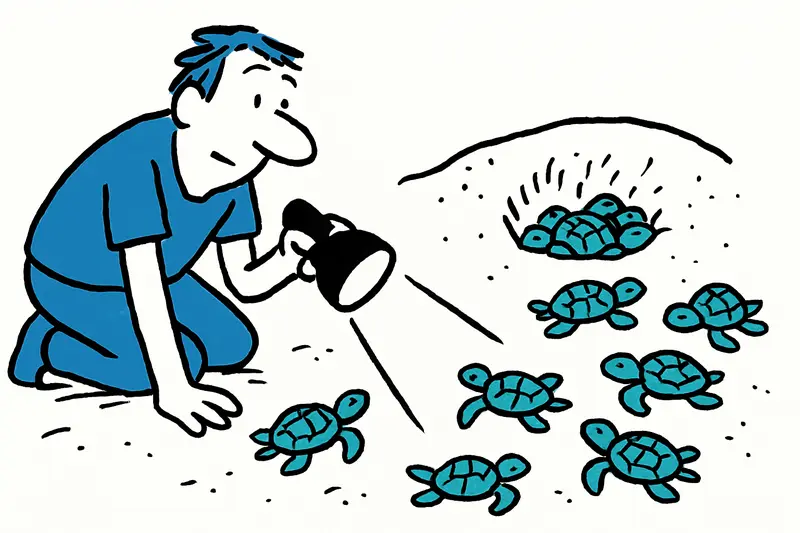

The salty wind blew across Can Pere Antoni, joggers crossed the promenade, and the city's lights flickered in the familiar evening glow. Between blankets and torches, however, something very different was happening during the night: 62 tiny loggerhead sea turtles crawled out of a clutch discovered in July and made their way to the sea. Volunteers, environmental agency staff and municipal responders watched over the site – as described in 34 crías en Can Pere Antoni: una tarde que da esperanza – with lukewarm coffee and held breath.

How the operation was organized

The nest was discovered in mid-July. Ten eggs went to artificial incubation, the rest remained on the beach, partly relocated to a protected spot. The first hatchlings emerged already on Friday, most during the night into Sunday. Teams from COFIB, the center „Aula de la Mar“ and the LIMIA research laboratory from Andratx handled registration, measurements and placement into the Head-Starting program, which accompanies the animals under controlled conditions for about ten to twelve months.

The question nobody likes to ask: is it enough?

Such images move people. But the central guiding question remains: Are night watches, incubation and head-starting sufficient to stabilize populations in the long run? In the short term: yes, they increase the survival chances of newly hatched animals. In the long term, however, the measures reach limits – especially on the beaches of an increasingly urban island.

Head-starting reduces early mortality. But what happens when the larger juveniles are released after months? Data on survival in the open sea and return rates to Balearic beaches are scarce. Besides natural predators, it is often man-made dangers – pollution, fishing nets, boat traffic, light pollution – that later threaten the juveniles.

Aspects that are rarely discussed enough

First: light pollution on urban coasts. Streetlights, promenade lighting and spotlights disrupt the orientation of freshly hatched turtles. A red filter on torches helps – but what good is that to the animal if the entire coast is lit at night?

Second: conflicts of use on popular beaches. Can Pere Antoni is a city beach: dogs, beach bars, walkers and events cross sensitive areas here. Night watches require volunteers and patience – both are scarce resources.

Third: the question of space. Nesting sea turtles need quiet, wide dune areas. In Palma these are increasingly fragmented. Stone revetments, promenades and private beach enclosures change the dynamics of the coastline.

Concrete opportunities and proposals

The good news: there are practical steps that authorities, citizens and tourism actors can take together.

1. Light management: Temporary shutdowns or dimmable lighting in nesting sections during peak hatching times; mandatory use of red filters for operations.

2. Beach use rules: Clear night-time exclusion zones, leash requirements and stricter controls for dogs during the nesting season; schedule events and installations so that nesting areas are respected.

3. Volunteer coordination: A central registry, fixed trainings and minimally paid coordinators could stabilize willingness to help – volunteering alone is not always enough.

4. Research and monitoring: Long-term studies on the survival rate of head-started animals; tagging and satellite transmitters for selected individuals to collect data on return and migration movements.

5. Coastal protection and dune restoration: More space for natural dunes, fewer hard coastal defenses, so beaches can again offer natural nesting conditions.

Why this matters for Mallorca

When 62 babies come into the world at Can Pere Antoni, it's a sign: protection measures work. But these success stories must not be an excuse for complacency. Mallorca is an island under strong use pressure – and protection needs planning, not just good feelings. Volunteers are indispensable; but without structural measures we remain in emergency mode.

Around 01:15 I saw helpers smile as small shells crawled over the dunes. The image will remain. It should, however, spur us to create the conditions so that the smile is not needed for just one night.

Similar News

Two years' imprisonment after tradesman fraud: Who pays for clients' protection?

A service technician in Palma was sentenced to more than two years in prison after defrauding several customers of advan...

Faster Than Expected: Terreno Barrio Hotel Opens in May – Opportunity for El Terreno or Another Push for Gentrification?

A new four-star hotel at Joan Miró 73/75 is set to open in May. 21 rooms, publicly accessible spaces and a gym for resid...

Father and Son Missing in the Tramuntana: Why Hikers Keep Getting Lost in the Mountains

Since Monday evening, mountain rescue teams around Escorca have been searching for a father and son who got lost in the ...

Why Mallorca's residents are moving to the mainland — a reality check

Housing prices in the Balearic Islands are pushing many locals to the Spanish mainland. What do the numbers show, what i...

Drug seizure in Santa Catalina: 116 plants, revolver and illegal electricity connection

In an apartment in the popular Santa Catalina district, the National Police discovered an indoor grow with 116 marijuana...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca