Trouble in Es Carbó: How many boats can the small bay handle?

Early in the morning it's obvious: motorboats pushed right up to the shallow shoreline. Residents in Es Carbó complain about noise, diesel fumes and damage to the coast. Time for clear rules, consistent controls and real solutions.

In the morning there's calm — and in the afternoon the engine hum

If you drive to Es Carbó in the early hours, the first thing you notice is the silence: gull calls, the clatter of light waves on the pebbles, the sun still low above Colònia de Sant Jordi. In the afternoons, however, the scene changes. Residents report that motorboats are increasingly being pushed up close to the shallow shore — some so near you could count the tapas on the foredeck from land, as described in Es Carbó between swimmers and anchor chains: Residents demand more controls.

The mood is tense. María (58), living in the settlement since 1989, says in a hoarse voice: 'On weekends it can sometimes be like a parking lot by the sea. Children can no longer play undisturbed, and the smell of diesel lingers in the air for hours.' It is precisely these details — the drone of generators, the occasional clouds of barbecue smoke, the improvised sun awnings — that turn a peaceful bay into a point of contention.

What is the central question?

The guiding question is simple: how much boat traffic can a small bay like Es Carbó tolerate without residents, fishers and the environment suffering? Behind the annoyance lies more than noise. It is about environmental impact, safety risks and fairness in public space. While tourism and boat rental businesses profit from spontaneous bathing fun, the situation is echoed in Trouble over license-free boat rentals: When Es Carbó becomes a racetrack. The people who live here suffer.

The complaints can broadly be grouped into three points: noise (music, generators), environmental risks (fuel residues, possible damage to the posidonia meadows) and the lack of infrastructure for mooring recreational boats. Fishers report that they often have to give way — a dangerous situation when there is more traffic in the bay than there is space.

What is often overlooked?

Two levels are often missing from the public debate: cumulative environmental damage and the institutional fragmentation of responsibilities. Small amounts of fuel or oil that regularly enter the water remain invisible to most bathers — over years they can damage the seagrass meadows that are essential nurseries for fish. And although many have the word 'protected area' on their lips, concrete controls are complicated: the municipality, maritime authorities and environmental agencies each pull different levers.

Another scarcely examined point is the local social dynamic. Visiting boaters, day-trippers and pensioners share a very limited space — and rules are often broken informally because sanctions are rare and hard to enforce.

Concrete solutions — what could help now

The residents' proposals are pragmatic and could form the basis for political action. In the short term, sensible measures would be:

- Targeted control times: patrols on weekends and holidays coordinated between the municipality, the coastguard and the local police.

- Visible sanctions: fines for illegal mooring on the shore, for open-barbecuing or illegal waste disposal.

- Strengthen documentation: report photos, times and boat identities — this creates solid evidence for interventions.

In the medium term, technical measures help: fixed mooring buoys that prevent boats from being pushed ashore, clearly signposted no-go zones, and defined anchor areas a little further out. Such solutions cost money but reduce conflicts and protect the posidonia.

In the long term, a clear distribution of roles is necessary: the municipality could issue local ordinances (e.g. time restrictions for anchoring), maritime authorities must enforce compliance on the water, and environmental agencies should carry out regular monitoring of seagrass beds. Cooperation instead of mutual finger-pointing would be the key here.

Why this matters for Mallorca

Es Carbó is just one small example among many, but it reveals larger dynamics: if the island continues to be shaped by spontaneous, unregulated boat traffic, not only individual residents will suffer — the quality of coastal ecosystems and thus tourism itself would be damaged in the long run. A balanced coexistence of recreational use and protection is not naive, but necessary.

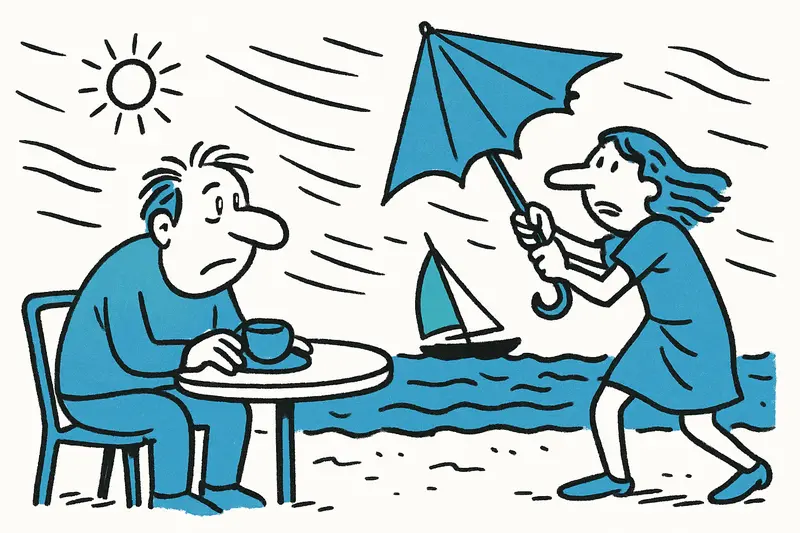

Discussions are already taking place locally: boat owners, fishers and residents meet informally on the small plaza by the bar, sometimes loudly, sometimes over coffee and a view of the sea. That is good — but it is not enough. Binding rules, clear responsibilities and the courage to impose sanctions when those rules are broken are needed.

If you observe something, you can help: send photos with time stamps to the municipality, note ferry or boat numbers. Documentation is often the first step toward effective measures.

The summer will show whether anger turns into constructive solutions — otherwise Es Carbó will soon remain only a postcard motif, but no longer a place where children can play undisturbed in the shallow water.

Similar News

Burger Week and Restaurant Week: How February Comes to Life on Mallorca

Sixteen venues compete for bites and likes: the Fan Burger Week (Feb 16–22) entices with special offers and a raffle to ...

Cause inflammation on contact: How dangerous are the processionary caterpillars in Mallorca — and what needs to change now?

The caterpillars of the processionary moth are currently causing trouble in pine forests and parks. Authorities are remo...

Teenager seriously injured on Ma-2110: Why this night road needs more protection

A 17-year-old was seriously injured on the Ma-2110 between Inca and Lloseta. A night road, lack of visibility and missin...

Storm warning again despite spring sunshine: what Mallorca's coasts need to know now

Sunny days, 20+ °C – and yet the warning system beeps. AEMET reports a yellow storm warning for the night into Tuesday f...

Final installment for the Palma Arena: a small weight lifts from the Balearics

The Velòdrom Illes Balears will pay the final installment of its large construction loan on July 13, 2026. For Mallorca ...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca