'Our bedroom sounds like a workshop' – Palma residents demand night flight ban

Nighttime aircraft noise on the Paseo de es Carnatge is driving residents onto the streets. Their central question: can a night-time quiet be enforced without endangering airport operations and the island's economy? A look at measurements, health risks and pragmatic solutions.

Can Palma win back the night?

On the Paseo de es Carnatge, where the sea usually has the last word, engines have been roaring for years. 'At four in the morning our bedroom feels like a workshop,' says María, who has lived on the coast for twelve years. On Saturday morning neighbors stood on the pavement with simple measuring devices, stopwatches and thermoses and counted take-offs and landings – minute after minute, they report, as reported in the article 'Sueño en vez de pista' on Palma's health and aircraft noise. The question now on the table is clear: how much aircraft noise can Palma tolerate at night, and how can the city effectively protect its residents?

Measurements, everyday life and invisible consequences

The initiative's own measurements show peak values outside that are well above what many consider tolerable. Inside bedrooms residents regularly report 60–75 decibels – levels that can disrupt sleep patterns. The WHO recommends around 40 decibels at night, the EU cites 55 decibels as a rough guideline. For many here that is just a jumble of numbers; what matters is waking up with a racing heart, babies who can't fall asleep, older people taking pills, and constant tiredness among those who have to work in the morning.

It's not only noise peaks that are counted but also frequency: three, four, five loud overflights in an hour – a series that slices sleep into several short segments. On the plaza in front of a bar pensioners discuss quiet hours, young parents speak of half-closed eyes while feeding bottles. These are sounds you hear – and long-term risks you barely see: stress, higher blood pressure and potential consequences for mental health.

What is often overlooked: distribution and the economy

Two aspects are missing from the public debate: first, the social distribution of the burden, and second, the economic context. Not all neighborhoods are equally affected; the coastal districts close to the approach path bear the main load. This often affects people who have no option to move away or swap into soundproofed apartments.

At the same time, the airport is a driving force for the island's economy. Hoteliers, small taxi businesses, restaurants and workers benefit from flights, even if many of them work during the day and need peace at night. The core question therefore is: can an effective night-time quiet be introduced without unduly impairing accessibility and jobs?

Technical, legal and organizational levers

A blanket ban from 23:00 to 06:00 is what residents have been demanding – a solution already practiced in other cities. But before sinking into black-and-white debates, it's worth looking at actionable steps:

Immediate measures: Trial night-quiet weekends as tests, intensified around-the-clock noise measurements with open data for the public, temporary restrictions on loud night departures (e.g. charter flights).

Medium-term approach: Prioritizing quieter aircraft types at night, stricter operating permits for particularly noisy machines, better approach procedures (less climb-and-descent noise), mandatory use of quiet taxiways during ground operations.

Long-term measures: Subsidy programs for soundproof windows and building insulation in the most affected neighborhoods, a fund for long-term health research in the Balearics, binding noise limits and an independent complaints and measurement network.

Who needs to talk – and who pays?

Responsibility is shared: city administration, island government, airport operator and air traffic control. AENA and similar operators can influence technology and slots; airlines decide on aircraft types and schedules. Politicians can set rules and provide subsidies. A fair solution needs a dialogue that does not stop at press releases: binding trial phases, transparent measurement data and clear criteria for when a permanent night flight ban is possible.

Financing solutions are feasible: subsidies for bedroom renovations from tourism levies, incentives for airlines to use lighter aircraft, or compensation payments to particularly affected neighborhoods. It is important that the burdens are not shifted entirely onto residents.

Outlook: a night that is a night again?

The mood in Palma is calm but tense. Many protesters say it is not against tourists or the airport per se, but about the right to restorative sleep. Practical solutions are possible – they require political will, technical adjustments and money. The critical guiding question remains: will politicians and operators dare to protect the night with real, verifiable measures, or will the Sunday counts in front of the Paseo remain symbolic?

Until an answer is found, people here close their windows, press earplugs into their ears and hope for quieter nights. The sea breeze still brings salt into the streets and the noise of planes – a reminder that quality of life also needs noise policy.

Similar News

Burger Week and Restaurant Week: How February Comes to Life on Mallorca

Sixteen venues compete for bites and likes: the Fan Burger Week (Feb 16–22) entices with special offers and a raffle to ...

Cause inflammation on contact: How dangerous are the processionary caterpillars in Mallorca — and what needs to change now?

The caterpillars of the processionary moth are currently causing trouble in pine forests and parks. Authorities are remo...

Teenager seriously injured on Ma-2110: Why this night road needs more protection

A 17-year-old was seriously injured on the Ma-2110 between Inca and Lloseta. A night road, lack of visibility and missin...

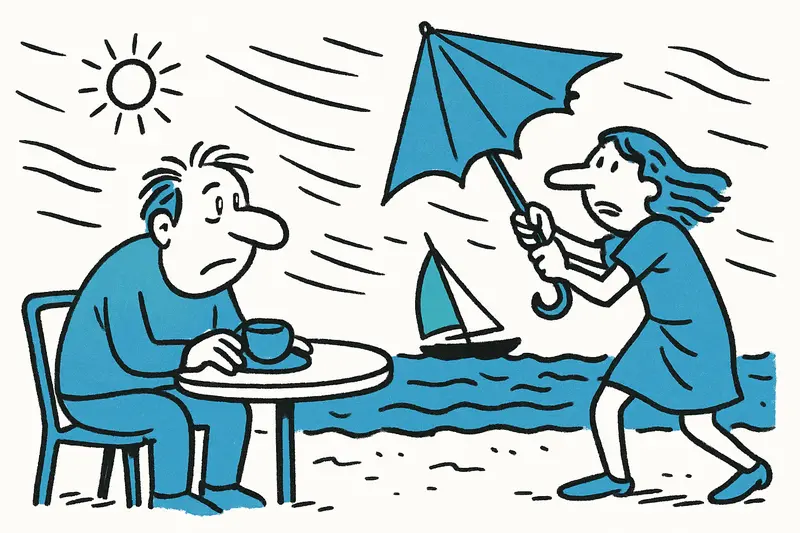

Storm warning again despite spring sunshine: what Mallorca's coasts need to know now

Sunny days, 20+ °C – and yet the warning system beeps. AEMET reports a yellow storm warning for the night into Tuesday f...

Final installment for the Palma Arena: a small weight lifts from the Balearics

The Velòdrom Illes Balears will pay the final installment of its large construction loan on July 13, 2026. For Mallorca ...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca