The Silent Guardians of Palma: When Protected Trees Are in Danger

Palma's old olives, figs and plane trees are living monuments – but protection doesn't automatically mean safety. Why some of these witnesses still suffer and what should be done.

City trees that tell more than a monument

When the church bells ring over the Plaça del Cort and the espresso steams at the corner, there it stands: the thick olive tree in front of the Ajuntament. People gather around it, take photos, lean against its trunk. You feel something that is hard to build into concrete – history. And it is precisely this history that the Balearic registry has tried to preserve since 1991: currently 76 protected trees in the Balearics, 50 on Mallorca, ten in Palma.

Key question: Is official protection really enough to save these trees?

It almost sounds idyllic: an office decides, a tree is placed on the list, and that's it. However, protection is not a static label but an assignment of work. Sometimes the city still loses witnesses. Remember the ombu on the Plaça de la Reina? It had been on the list since 2003 – and split in two in 2019. That shows: an entry alone does not protect against age, disease or sudden storms, as reported in When Palma's Trees Fall Silent: Felled Pines and Lost Trust.

What often gets lost in everyday life: many protected trees stand on private land. The law does require permits for pruning and prescribes special care, but implementation depends on owners, administrative capacity and money. A tree may be protected on paper – in practice it needs maintenance, space for roots and sometimes a new tree pit that is not crushed by a pavement, a reality echoed in Alarm in Palma: Neighborhood Resists Tree Felling on Plaza Llorenç Villalonga.

Aspects we rarely hear

First: soil sealing. Paved areas around a tree, parking spaces, underground utilities – these suffocate roots. Second: climate change and new pests. Longer dry periods and warmer winters change the disease dynamics of fungi and insects. Third: bureaucratic delays. If a huge crown appears acutely at risk of breaking, quick decisions are needed – but approval processes can take weeks, a problem made visible during the Dispute over 17 Ombu Trees on Plaza Llorenç Villalonga: Who Decides on Urban Green?.

And fourth: knowledge and appreciation diverge. Some people see the old rubber tree in the cemetery as just a provider of shade, others as a centuries-old witness. Without public education, there is often little willingness to invest.

Concrete trouble spots in Palma

Notable protagonists include: the sturdy olive at the Ajuntament, the huge fig in the courtyard of La Misericòrdia, the rubber tree at the Cementiri, the Chinese jujube in the Convent de la Concepció and the legendary "Na Capitana" of Son Muntaner. These trees need more than a sign: they require planned watering, regular specialist care, protection zones against compaction and a readiness to act quickly in case of damage.

What would help concretely

First: a local emergency fund for urgent tree care. If a crown changes dramatically, responsibility must not stall in months of administrative rounds. Second: maintenance contracts with specialized arborists and training for municipal gardeners – this is not a luxury but prevention. Third: removing paving around old trunks and flexible pathways instead of straight slabs. Fourth: incentives for private owners to invest in their trees – tax breaks or grants could help.

Technology helps too: tree sensors for moisture and root stress, digital maps where any resident can report damage, and interpretive panels that tell people why one olive is older than their great-grandmother. Such measures strengthen identification and create pressure for protection.

Short-term needs also include pragmatic changes: a procedure for emergency pruning with mandatory subsequent evaluation, faster expert teams and a clear liability rule between owner and municipality. In the long term Palma needs a tree strategy that thinks together climate resilience, biodiversity and the urban landscape.

When you sit under the dense foliage of that fig in the courtyard on hot August days and the city sounds become muffled, you realize how precious that shade is. The trees are not just green: they are archives, air conditioners and silent chroniclers. It would be a pity if they remained merely entries on a form while their needs disappear under asphalt.

The central question remains: do we really want to protect our living monuments – or is it enough for us to feel good about seeing them on a list?

Similar News

27 years, a 'Yes' and the island as witness: Peggy Jerofke and Steff Jerkel celebrate on Majorca

After a long period of ups and downs, Peggy Jerofke and Steff Jerkel plan to marry on June 26 in the east of Majorca. A ...

Jan Hofer on Mallorca: Homesick for Wholegrain — Yet Settled

The 75-year-old TV veteran lives on the island with his wife, takes small homeland trips to Can Pastilla and sometimes m...

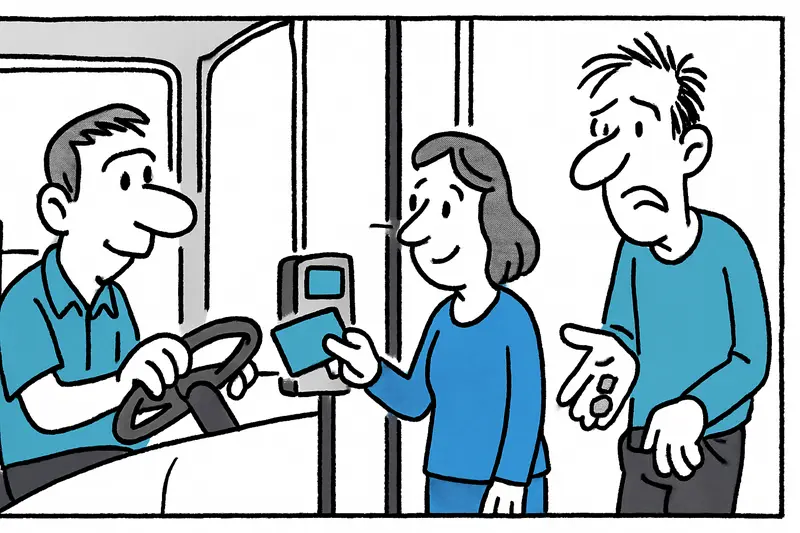

Card payments on Palma's city buses – relief or nuisance?

EMT is rolling out card readers in Palma's buses: about 134 vehicles already equipped, group discount rules — but also t...

Knee-high water at Playa de Palma: What to do about the recurring floods?

Torrential rainfall flooded the Playa de Palma, with walkways knee-deep in water. An assessment of what's missing and ho...

Llucmajor gets beaches ready: new signs, pruned palms and preparations for the summer season

Llucmajor is preparing for the bathing season: palms in s'Arenal have been trimmed, 16 bathing areas will receive inform...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca