Cala Romàntica: 77 houses approved — Manacor's last natural area at risk

Manacor has approved the construction of 77 single-family homes near Cala Romàntica. Residents are left with questions about water, traffic and nature — and the search for solutions.

Cala Romàntica: Approval after decades — but what remains?

The decision was made more quietly than expected, on a windy morning when the pines at Cala Romàntica smell of the sea again and the seagulls circle over Punta Reina. The municipality of Manacor has approved the construction of 77 single-family homes on an area of around 100,000 square meters. For many this sounds like the final step of a development that has been in the files since the 1970s, a pattern described in Half-built walls are becoming holiday homes again: 159 units, hundreds of reservations — and an old conflict rekindled. For others, it is the end of one of the last contiguous open spaces on this coast.

What lies behind the decision?

Generous plots with minimum sizes of 800 square meters are planned, distributed over the site near the Punta Reina complex. A developer from Madrid has submitted variants for years, modified them and adapted to conditions — now the papers are in and the administration has given the green light. One sticking point: parts of the area were previously designated as green zones and were transferred to the city. This makes the procedure legally complex and complicates clear stops by the council; concrete mixers disturbing the peace in nearby bays has already been reported in Dream cove amid construction noise: s'Estany d'en Mas between pines and concrete.

The central question: Is this really still necessary?

This question is not only in the files but also among locals: at the kiosk on the promenade, on the plaza and under the pines you hear it in many different tones. Some residents fear more traffic, higher pressure on already scarce water resources and a further loss of natural coastline. Others see construction and investment as an opportunity — investments, jobs, a better fiscal base for the municipality, a sequence that already included Manacor close by: Ten capped apartments — a start with many questions. But the debate remains unbalanced: those who build later often have the stronger legal arguments, while those who have lived here a long time have the stronger emotions.

Less illuminated aspects

Public discussions often lack detailed questions that can become painful later. For example: What are the consequences of additional soil sealing for the local microclimate? Who will pay for upgrading the narrow access roads if suddenly 150 more vehicles use them daily? And: How hot will it get in the new settlements in August when rainwater runoff is blocked and the heat lingers longer?

Another often overlooked topic is ecological connectivity. Small fallow plots, hedges and cork oak lines function as lifelines for insects, lizards and birds. If they are cut up, biodiversity declines in the long term — not just a romantic problem, but a practical one: fewer pollinators, less natural pest control, less shade on hot days.

Concrete solutions that should be discussed now

The decision has been made, but the design is still pending. The town hall and planners could make measures mandatory that represent real compromises:

Water and wastewater: Mandatory rainwater retention and greywater recycling for garden irrigation; connection to modern, releasable treatment plants; independent load assessments before construction begins.

Traffic: Traffic calming plans, one-way systems, mandatory bicycle parking, car-sharing offers and shuttle solutions during the high season so that not every household makes two additional cars the norm.

Sealing and greenery: Surface limits, mandatory permeable pavements, minimum quotas for native planting and binding ecological corridors that preserve existing hedges and tree lines.

Phasing and control: Order construction in staggered phases tied to demonstrable infrastructure improvements; independent environmental controls and transparent citizen participation at milestones.

What remains to be done — local and visible

The decision is not an end point but the start of a concrete negotiation about quality. Manacor faces a task that is most noticeable in the small things: in the morning sounds of construction vehicles, in conversations at the little supermarket or on the promenade when the heat shimmers and the air smells of pine resin. If the municipality does not now set clear, verifiable rules, the new houses risk becoming another fragment on the map — nicely packaged but ecologically and socially problematic.

The clock is ticking: this is not just about houses, but about how we want to live on this coast. Who pays the price: nature, the neighborhood or the public purse?

The coming months will show whether the administration, the developer and the residents find a real compromise — or whether Cala Romàntica will lose a piece of its calm while the planning work continues on paper.

Similar News

27 years, a 'Yes' and the island as witness: Peggy Jerofke and Steff Jerkel celebrate on Majorca

After a long period of ups and downs, Peggy Jerofke and Steff Jerkel plan to marry on June 26 in the east of Majorca. A ...

Jan Hofer on Mallorca: Homesick for Wholegrain — Yet Settled

The 75-year-old TV veteran lives on the island with his wife, takes small homeland trips to Can Pastilla and sometimes m...

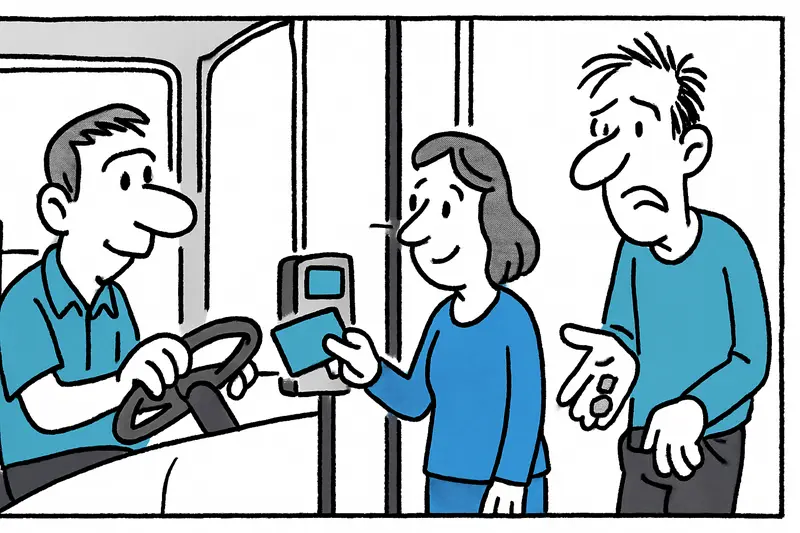

Card payments on Palma's city buses – relief or nuisance?

EMT is rolling out card readers in Palma's buses: about 134 vehicles already equipped, group discount rules — but also t...

Knee-high water at Playa de Palma: What to do about the recurring floods?

Torrential rainfall flooded the Playa de Palma, with walkways knee-deep in water. An assessment of what's missing and ho...

Llucmajor gets beaches ready: new signs, pruned palms and preparations for the summer season

Llucmajor is preparing for the bathing season: palms in s'Arenal have been trimmed, 16 bathing areas will receive inform...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca