When Children Become 'Occupiers': How Care Becomes a Backdoor into Real Estate

When help turns into possession: In Palma there are increasing cases in which relatives who move in to provide care no longer move out. What does this mean for heirs, the law and the housing market?

When caregiving becomes the entry ticket

A morning in Palma: the sun peeks over the cathedral, on Carrer de Sant Miquel it smells of freshly brewed coffee and a neighbor waters her plants. "The daughter has been here for months now," María says from the balcony, listening to voices from the stairwell. "She looks after the mother — and she won't pack up when the woman dies." I've been hearing sentences like this more often in recent weeks: stories that oscillate between compassion and suspicion. These conversations sometimes intersect with other housing problems such as When Long-Term Tenants Turn into Holiday Landlords: The Inquilinos Pirata in Mallorca.

The key question: help or takeover?

What is this really about? In short: when relatives move in to provide care, the apartment sometimes turns into a de facto takeover. First come the shopping trips, sitting by the bedside, the prescribed medication. Then comes furnishing, taking over the mail, sometimes paying bills — and finally insisting on staying. Many ask themselves: when does caregiving end, and when does a new, factual property situation begin?

What everyday life on the island reveals

Behind the cases are two simple drivers: expensive property and scarce housing. Young families and siblings who claim an inherited apartment rarely find quick alternatives. At the same time the island has aged; nursing homes are expensive and organizing professional care is difficult. This mirrors reports like When Living Rooms Become Bedrooms: How Mallorca Suffers from a Housing Shortage. The result: whoever has the time moves in. Sometimes out of care, sometimes out of calculation.

The legal situation is often unclear

The law provides rights for co-heirs, but practice is complicated. Customary law, usufruct issues and questions about who covered costs for how long delay decisions. The system also protects the vulnerable: minors or people with disabilities can trigger administrative barriers — evictions take time. Lawyers in Palma report that case numbers are rising because housing is scarce and property represents a value that some do not want to let go of. This trend coincides with broader pressures such as Housing Price Shock in Mallorca: How Legal Large Rent Increases Threaten Tenants.

What is missing from the public debate

The story is often told as a personal conflict between siblings — but too rarely as a symptom of a structural problem. It's not just about individual "occupiers" within families, but about an intersection of inheritance law, care needs and a market that pushes young people and middle incomes out of the towns, as shown by When Rent Decides: How Villages Lose Their Families. The role of municipalities is also underexposed: what options does the ayuntamiento have to intervene or mediate?

Practical steps for those affected

Those affected now should act systematically: collect documents (bank statements, rent payments, witnesses), seek legal advice early and try to resolve conflicts out of court first. A simple written care agreement or a pre-arranged contract can later prevent great harm. Some neighbors recommend involving social services or municipal mediation — often neutral moderation eases tensions more than an immediate lawsuit.

Solutions for the island

At a structural level we need several levers at once: more affordable housing, clearer legal rules for temporary residential rights in the context of care, and low-threshold mediation services in the municipalities. Concrete ideas might include:

- Mandatory written care agreements: A simple, notarized agreement between owner(s) and the caregiver could clarify expectations and make abuse harder.

- Municipal care pools: If municipalities offer low-cost support for home care, the pressure to privately occupy apartments would decrease.

- Rapid mediation centers: An office in the ayuntamiento that mediates family housing conflicts could shorten processes and prevent escalations.

Why this matters for Mallorca

This is not an abstract legal problem but a slice of everyday life: at the market in Santa Catalina, in cafés on the Paseo Marítimo, in stairwells with the typical mix of voices, sea breeze and the clatter of buses. Without clearer solutions, the number of such stories will continue to grow — and with them the mistrust within families and neighborhoods. Similar dynamics have driven older residents away in pieces like When Rent Becomes a Farewell Letter: How Rising Housing Costs Are Driving Pensioners off Mallorca.

A final piece of advice — and a wish

In the end you often hear the same, banal but true advice at the supermarket checkout or the kiosk: talk to each other, put things in writing — before it's too late. That won't romanticize the situation, but it will make it less hurtful. And perhaps, very quietly, politics should listen here too: not every occupier is a criminal, but every untreated problem will make the island a little harder.

Similar News

27 years, a 'Yes' and the island as witness: Peggy Jerofke and Steff Jerkel celebrate on Majorca

After a long period of ups and downs, Peggy Jerofke and Steff Jerkel plan to marry on June 26 in the east of Majorca. A ...

Jan Hofer on Mallorca: Homesick for Wholegrain — Yet Settled

The 75-year-old TV veteran lives on the island with his wife, takes small homeland trips to Can Pastilla and sometimes m...

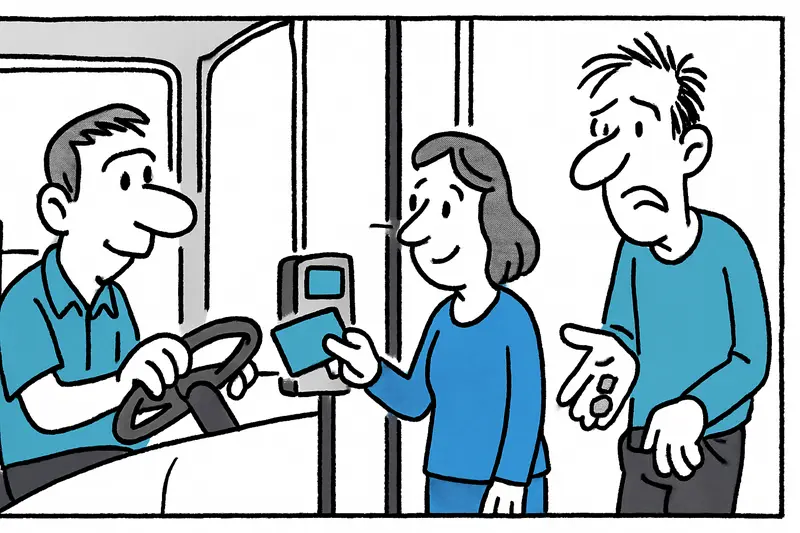

Card payments on Palma's city buses – relief or nuisance?

EMT is rolling out card readers in Palma's buses: about 134 vehicles already equipped, group discount rules — but also t...

Knee-high water at Playa de Palma: What to do about the recurring floods?

Torrential rainfall flooded the Playa de Palma, with walkways knee-deep in water. An assessment of what's missing and ho...

Llucmajor gets beaches ready: new signs, pruned palms and preparations for the summer season

Llucmajor is preparing for the bathing season: palms in s'Arenal have been trimmed, 16 bathing areas will receive inform...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca