More Refugee Boats in the Balearic Islands: When the Ports Do Not Rest at Night

Over 5,900 people have reached the Balearic Islands in small boats this year. While volunteers hand out tea from thermoses at night, communities ask: How long can the system hold up before supply, health and integration suffer?

When the night at the harbor grows long: More people in small boats in the Balearic Islands

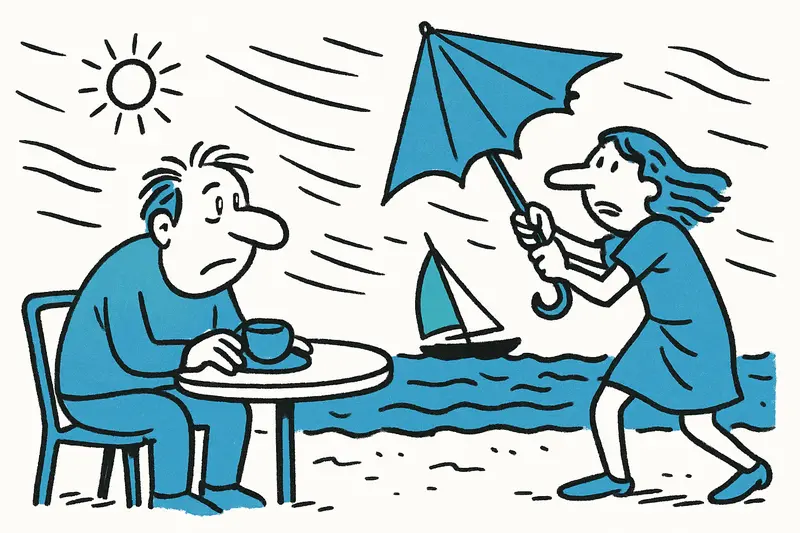

The raw numbers stand like a date stamp: more than 5,900 people have already arrived this year in small, often overcrowded boats on the Balearic Islands, as reported in More Boats, More Questions: Mallorca Under Pressure from Rising Boat Arrivals – slightly more than in the whole of 2024 (just under 5,882). In the ports you notice it not only in statistics but in small, everyday scenes: lantern light on wet decks, the distant hum of a boat engine, the croaking of seagulls and volunteers who still hand out tea from thermoses at midnight. Long queues form on the promenades, blankets pile up in sports halls, and the mood swings between practiced routine and worried exhaustion.

Key question and situation assessment: How long can the islands keep up the pace?

Key question: How long can small island communities like Formentera or ports like Port d’Alcúdia cope with the increased pace of arrivals without supply, healthcare and integration processes suffering? The answer is complex. On one hand there are experienced rescue teams (see New surge of boat migrants: 122 people rescued in one day off the Balearic Islands) and well-organized volunteer groups, on the other hand limited beds, scarce personnel resources and tight municipal coffers.

The season varies – spring and early summer are traditionally stronger, but the experiences from 2024 remain in mind: between October and December more than 2,700 people arrived. That means: even if temperatures are mild and tourists sip iced coffee, the last quarter can still double the strain.

What is often overlooked on site

The public debate is dominated by numbers and processing at the port, but many costs remain invisible. Interpreters, psychosocial first aid, administrative registration and medical follow-up are time-consuming and personnel-intensive. Small municipalities have to pull staff from schools, social services and health centers – then a routine task suddenly becomes a bottleneck: a school renovation is postponed, rooms are needed as emergency shelters, appointments at health centers are pushed back.

There is also an information gap. Residents, dockworkers or café owners see queues and wonder what is happening. If official communication remains vague, rumors and uncertainty grow – fertile ground for prejudice. What is needed here are transparent, short-term updates on procedures, expected length of stay and available support services.

Concrete challenges at the ports

The spatial constraints of island ports are a real problem: limited beds in temporary shelters, cramped terminal areas and only sporadic options for initial medical care. Night landings make everything more complicated: lighting, security concepts and access to interpreters are not automatically available at night. Volunteers report improvised night shifts in which they hand out blankets, soothe babies and apply simple bandages – guided by experience, but also by exhaustion.

Less discussed opportunities and pragmatic solutions

The situation is serious, but not hopeless. Many measures can be implemented locally and primarily require coordination rather than large budgets:

1. Island-specific emergency plans: Each municipality should designate fixed contingents of community rooms, sports halls or cultural centers as short-term shelters – with clear checklists for logistics, sanitation and fire safety.

2. Mobile medical units: Small, deployable teams in containers or clinic vans can provide initial care, vaccination checks and wound treatment without blocking local hospitals.

3. Central volunteer database: A coordinated platform that maps availability, language skills and qualifications of helpers reduces improvised shifts and facilitates rostering.

4. Faster distribution mechanisms: Agreements between island and mainland authorities and cooperation with ferry companies could enable accelerated distribution of those receiving initial care once medical checks are completed, a path urged by local authorities in When Beaches Become Emergency Wards: Balearic Islands Call on the EU for Help in the Migration Crisis.

5. Strengthened neighborhood communication: Regular information meetings in communities, notices in ports and short, transparent press or social media updates build trust and reduce uncertainty.

In addition, medium-term solutions would be important: shared personnel pools for health and social services on the islands, targeted training for volunteers in trauma first aid and a flexible budget reserve for municipalities in emergencies.

Why the coming weeks are decisive

Whether numbers continue to rise depends on wind, weather and geopolitical developments; these trends are monitored by UNHCR Mediterranean situation. Local helpers are preparing – with flashlights, thermoses and phone lists of interpreters. Many have routine; but routine has limits when space and staff are stretched.

The challenge is not only numerical but organizational and social: more than quick intake numbers are needed – clear procedures, coordinated resources and open communication with the neighborhood are required. If municipalities, authorities and volunteer initiatives pool their forces, many problems can be mitigated. If uncertainty remains, the strain grows – and you feel it on the promenades when the night at the harbor becomes longer than usual.

Between harbor lights and quiet beaches, people here prepare – pragmatic, tired and with a large dose of experience.

Similar News

New vacation photos: Royal family in Mallorca — train ride to Sóller and visit to Esporles

The Royal Household has released previously unpublished family photos from the summers of 2012 and 2013 — intimate snaps...

Burger Week and Restaurant Week: How February Comes to Life on Mallorca

Sixteen venues compete for bites and likes: the Fan Burger Week (Feb 16–22) entices with special offers and a raffle to ...

Cause inflammation on contact: How dangerous are the processionary caterpillars in Mallorca — and what needs to change now?

The caterpillars of the processionary moth are currently causing trouble in pine forests and parks. Authorities are remo...

Teenager seriously injured on Ma-2110: Why this night road needs more protection

A 17-year-old was seriously injured on the Ma-2110 between Inca and Lloseta. A night road, lack of visibility and missin...

Storm warning again despite spring sunshine: what Mallorca's coasts need to know now

Sunny days, 20+ °C – and yet the warning system beeps. AEMET reports a yellow storm warning for the night into Tuesday f...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca