Huge gap in the registry: Nearly 8,000 unregistered holiday apartments in Mallorca

An analysis by the island council finds around 8,000 listings for holiday apartments that are not in the official registry. This strains neighborhoods, drives up rents and creates organizational and fiscal problems for municipalities. How can oversight be organized practically and fairly?

Nearly 40 percent not in the registry: The numbers behind the morning stroll

When you stroll through Palma's lanes early in the morning — Plaza Mayor still quiet, the baker already opening, a moped buzzing by — you feel the island's double reality: warm light, tourism offers on every corner. Current evaluations by the island council, including new maps showing hotspots of unregistered holiday apartments, now reveal that significantly more apartments are being offered than the authorities record. In an analysis of around 400,000 listings over twelve months, nearly 8,000 apartments stood out as missing from the official registry.

This is more than an abstract number. Extrapolated to sleeping places, we're talking about well over 40,000 potentially affected overnight stays. People arrive, do not always pay the correct charges, and their presence often remains invisible to authorities and neighbors. Trash bins fill faster, streetlights burn later into the night — a daily impression residents in Portixol and Santa Catalina confirm.

Key question: Why does control fail?

The central question is simply put: why do so many offers remain outside official control, even though a registry exists? The investigation used large data sets — investigations of illegal holiday listings in Mallorca, price trends, availabilities — and revealed discrepancies that have administrative and structural causes.

One reason lies in the economic logic: short-term rental pays off, especially in popular locations. Those who rent to tourists short-term instead of to a long-term tenant often earn higher income. Then there are legal grey areas — who is responsible, the owner, the manager, the agency? — and technical obstacles: platforms do not always report completely, and manual checks are slow. For example, Airbnb said it will remove listings without a registration number.

The consequence: municipalities lose revenue needed for sewage, street cleaning and services. At the same time, housing shortages worsen because housing suitable for long-term use is converted into tourist offers. Families, students and workers who can no longer afford housing in popular neighborhoods feel this.

What has been insufficiently discussed so far

Besides the well-known points, three aspects are often left out of the public debate: first the seasonal distribution — many unregistered offers are only active in peak times, but these peaks change daily life permanently. Second the role of data and automation: authorities could react faster with automatic matching procedures, but often lack staff or technically uniform systems. Third the cascade of appeals and legal procedures: a fine is quickly imposed, but procedures drag on, and landlords quickly change platform or listing.

This means: individual measures such as deletions help in the short term but do not address the root of the problem. In the long run, structured tools and a rethink in regulation are needed — less chaos, more clear processes.

Concrete approaches — practical instead of purely punitive

So what to do? Some possible steps that should be discussed on the island: first, a mandatory interface between platforms and the registry so that listings are automatically checked against the registry and non-compliant offers are immediately flagged. Second, a central municipal reporting system for short-term rentals with clear deadlines and simple penalties that are quickly enforceable.

Third, capacity building in municipalities: more staff for digital controls, shared databases between municipalities and the island council, and pilot projects in particularly affected neighborhoods. Fourth, fiscal and social incentives to return properties to the long-term housing market — for example temporary tax relief or subsidies for landlords who rent to residents.

Important is a fair balance: repression alone shifts the problem or drives local small providers into illegality. A mix of reporting requirements, digital controls and incentives could be more sustainable and relieve neighborhoods more quickly.

Who bears responsibility?

Responsibility does not lie only with owners or platforms. Municipalities must provide clear processes, regions must set technical standards, and platform operators must be more transparent. At the same time, we need a societal debate about what kind of tourism we want — the nightly transit point or lively neighborhoods with permanent residents?

The coming months will show whether authorities can keep up the pace. For many residents the hope remains that their neighborhood becomes more of a home than a transit point — and that the authorities close the gaps in the registries that have so far left so many unwanted traces.

Similar News

Burger Week and Restaurant Week: How February Comes to Life on Mallorca

Sixteen venues compete for bites and likes: the Fan Burger Week (Feb 16–22) entices with special offers and a raffle to ...

Cause inflammation on contact: How dangerous are the processionary caterpillars in Mallorca — and what needs to change now?

The caterpillars of the processionary moth are currently causing trouble in pine forests and parks. Authorities are remo...

Teenager seriously injured on Ma-2110: Why this night road needs more protection

A 17-year-old was seriously injured on the Ma-2110 between Inca and Lloseta. A night road, lack of visibility and missin...

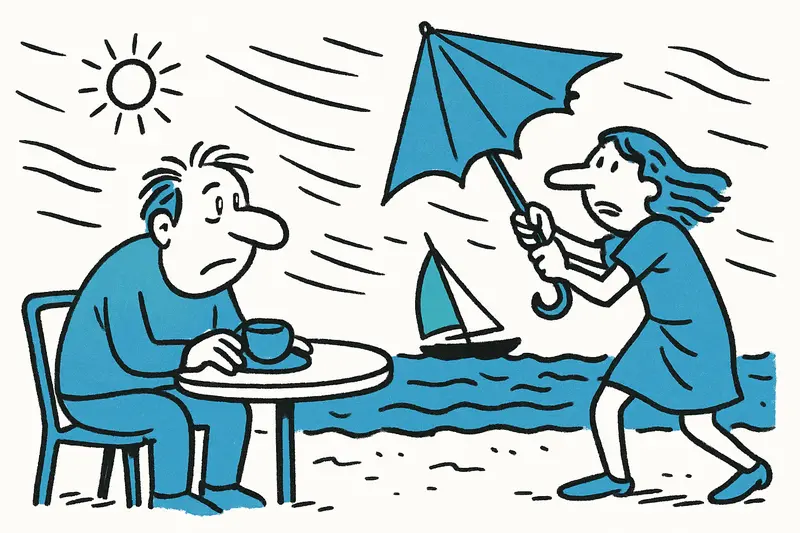

Storm warning again despite spring sunshine: what Mallorca's coasts need to know now

Sunny days, 20+ °C – and yet the warning system beeps. AEMET reports a yellow storm warning for the night into Tuesday f...

Final installment for the Palma Arena: a small weight lifts from the Balearics

The Velòdrom Illes Balears will pay the final installment of its large construction loan on July 13, 2026. For Mallorca ...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca