When the 'mümmels' are no longer manageable: Stray cats at Ballermann and what to do now

Residents near Playa de Palma report rapidly growing cat colonies. Between vacant lots, beach bars and the highway, feeding spots, lack of neutering and unclear responsibilities cause disputes. A humane, coordinated strategy with TNR campaigns, hotspot mapping and clear rules for those who feed could be the solution.

Between chair-clattering and gull cries: The cat colonies are growing — and nobody feels properly responsible

When the beach bars stack their chairs early in the morning and the cleaning crews sip their first coffee at Playa de Palma, the cat migrations begin along the embankments. Groups of animals, sometimes 5, sometimes 20, appear — between badgers, vacant plots and the highway toward Llucmajor. Residents who have lived on the coast for years say: it has become noticeably faster in recent months, as reported in Residents' complaints about cats at Ballermann.

The central question: How do you prevent compassion from becoming a colony?

The problem is not purely an animal control issue, but a social puzzle. People bring food scraps — out of pity, out of habit, because they seek a piece of home abroad. Some residents in makeshift accommodations in Can Pastilla or Las Maravillas set up permanent feeding spots to prevent hunger. That is understandable. But these very spots act like magnets: they enable colonies, increase reproduction rates and create conflicts with neighbors.

The consequences are concrete: increased droppings on paths, nighttime territorial fights with loud squabbling, traffic accidents when a cat crosses the road — and a neighborhood that grows weary because morning hygiene and sleep are disturbed. Many do not call for drastic measures, but for control and responsibility. The guiding question remains: Who takes responsibility — the city, animal welfare organizations, or the feeders themselves?

What is often overlooked

Two things are seldom discussed in public debate: first, the role of social poverty and homelessness as drivers of feeding, and second, the organizational hurdles faced by small animal welfare groups. People who travel outside the city to feed cats often seek human contact as well. Those living in precarious housing set up fixed spots out of care. At the same time, many local protection groups simply lack the funds for large neutering campaigns — and coordination with the Ayuntamiento is sluggish.

Another blind spot: feeding stations run without rules attract not only cats but also rats if not kept clean. This brings hygiene into focus, and neighborhoods quickly feel overwhelmed.

Concrete, humane solutions — and why they could work

One path is TNR (Trap-Neuter-Return) — trapping, neutering, returning. Technically proven, effective and comparatively inexpensive if organized. But TNR needs structure: mobile neutering actions, priority-setting for hotspots and a database of who feeds where.

Proposal for a pilot project at Playa de Palma:

1. Hotspot mapping — Use community lists from neighborhoods to map hotspots. The photos and reports neighborhood groups are already collecting are worth their weight in gold.

2. Mobile neutering clinic — A vehicle or temporary station supported by municipal grants and veterinarians offering low-cost surgeries. Student help from veterinary departments could assist.

3. Registered feeding stations — Instead of bowls everywhere, establish a few controlled feeding spots: with wind protection, waste containers and clear cleaning rules. Those who feed must be registered and take responsibility.

4. Education and social work — Training for feeders, raising awareness about hygiene and, instead of fines, prefer social work that offers alternative support — for example for people in precarious accommodation.

5. Transparent targets — Measurable KPIs: reduction of unneutered animals by X percent within a year, fewer complaints about noise or droppings, fewer traffic accidents in affected sections.

What the city must do — and what the neighborhood can contribute

The city administration can initiate programs, but it needs local backing: volunteers to care for feeding spots, local businesses providing spaces for mobile clinics, and clear communication. Neighborhoods, in turn, must be willing to accept uncomfortable truths — for example, that short-term feeding worsens the long-term problem.

An example from other regions, such as Llubí's ordinance requiring cat neutering and pet limits, shows: if all parties cooperate, colonies can be stabilized and conflicts significantly reduced. In Mallorca this could mean: fewer cats dashing across the road, less nighttime quarrelling and cleaner paths — without cruel methods being used anywhere.

It takes courage to coordinate and a bit of neighborhood spirit. If the bowls keep being left out, the whole community will ultimately pay the price — in noise, hygiene and quality of life.

Similar News

27 years, a 'Yes' and the island as witness: Peggy Jerofke and Steff Jerkel celebrate on Majorca

After a long period of ups and downs, Peggy Jerofke and Steff Jerkel plan to marry on June 26 in the east of Majorca. A ...

Jan Hofer on Mallorca: Homesick for Wholegrain — Yet Settled

The 75-year-old TV veteran lives on the island with his wife, takes small homeland trips to Can Pastilla and sometimes m...

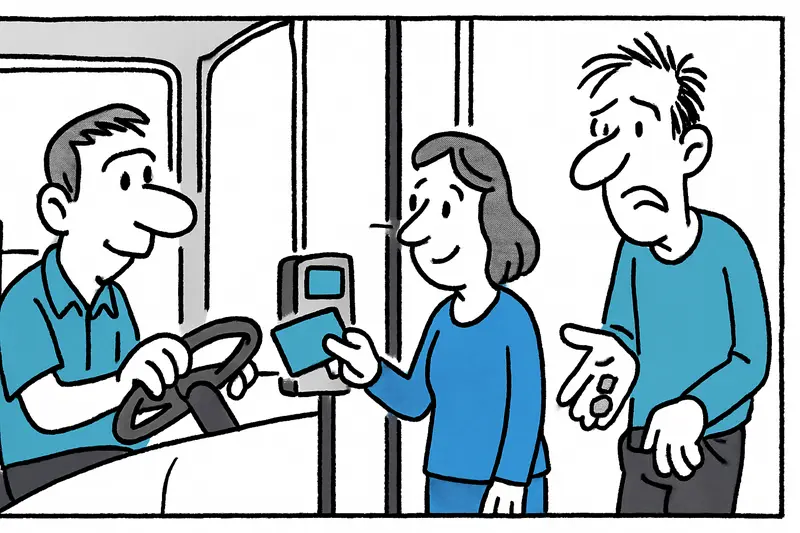

Card payments on Palma's city buses – relief or nuisance?

EMT is rolling out card readers in Palma's buses: about 134 vehicles already equipped, group discount rules — but also t...

Knee-high water at Playa de Palma: What to do about the recurring floods?

Torrential rainfall flooded the Playa de Palma, with walkways knee-deep in water. An assessment of what's missing and ho...

Llucmajor gets beaches ready: new signs, pruned palms and preparations for the summer season

Llucmajor is preparing for the bathing season: palms in s'Arenal have been trimmed, 16 bathing areas will receive inform...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca