Sóller faces a housing shortage: When neighbors can no longer find an apartment

The bells ring, the market smells of oranges — and the question remains: how long can Sóller still keep the people who make the place what it is, when apartments start at €1,500? A look at the numbers, missing tools and practical levers.

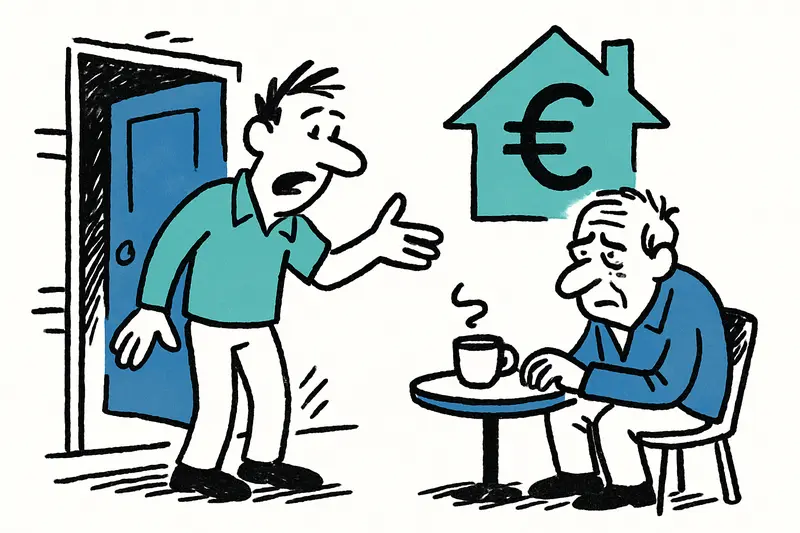

How long can Sóller still keep its people? When a neighbour can no longer find an apartment

In the early morning, when the bells of the Iglesia Sant Bartomeu are still reverberating and the Plaça Constitució smells of fresh coffee and warm bread, life runs as usual — at first glance. The Ferrocarril clatters up to the mountains full of commuters, the tram whistles up from the Port. But under the sun a different pattern emerges: households doing the sums, tradespeople planning the rest of the month after payroll, and more and more listings that start at around €1,500 a month. The key question remains: how can Sóller remain livable for those who work here and want to grow up here?

What the numbers show — and hide

Researchers and local data analysts evaluated nearly 950 rental contracts. A model would set a price of around €976 for a 96 m² apartment in the centre, and about €966 for an 84 m² apartment in the harbour area. Theory: roughly €900 on average. Practice: offers start at €1,500 — not an outlier, but the new normal. Within a decade property prices rose by about 182 percent, while wages increased by only around 29 percent. You can feel that in the streets: shuttered old building windows next to immaculately renovated holiday apartments. This mirrors findings in When Living Rooms Become Bedrooms: How Mallorca Suffers from a Housing Shortage.

Everyday life complains

At the market amid orange stalls, the cries of gulls and the chatter of tourists, vendors say they have to live elsewhere because they can no longer afford Sóller. A young bricklayer says he counts every euro before even thinking about children. An older woman who has swept the Plaça for decades has lost three neighbours in two years. “For many here, affordable housing is simply out of reach,” says a local geographer who analysed the data. This is more than statistics: it is the loss of social networks, spontaneous help when opening a shop, shared dinners — things that hold the place together. Similar dynamics are documented in Sky-high prices, tents, empty promises: Why Mallorca's housing crisis is no longer a marginal issue. More information on this problem can be found at Ways out of the housing shortage in Mallorca.

Why simple answers are not enough

The call for classification as a tense housing market keeps coming up. It is an instrument, but not a cure-all. Rent caps alone fall short when housing is simultaneously converted into holiday apartments, existing stock stands empty and speculative purchases dominate the market. Other less discussed aspects are also crucial: lacking controls on short-term rentals, opaque ownership structures, seasonal demand, basic services for seasonal workers and the tax logic that makes short-term renting more attractive than long-term leasing to locals. Current developments on these topics are examined in more detail at Housing in crisis.

Levers that promise to work — but not without courage

Sóller is discussing various measures. Some are already familiar, others are too rarely elaborated in the debate:

1. Rent and vacancy registers: A reliable database is a prerequisite. Only those who know which apartments are truly vacant or repeatedly offered as holiday rentals can act in a targeted way.

2. Tax differentiation: Higher levies on permanently vacant or exclusively tourist-used properties; tax relief for owners who rent long-term to local families. That would shift economic incentives toward permanent use.

3. Support programmes for renovating existing stock: Funds for the refurbishment of old apartments, coupled with occupancy obligations for locals. This way facades, cobblestones and the social fabric can be preserved.

4. Municipal intermediary renting and buybacks: If the municipality selectively buys individual properties or makes them available through intermediary renting, pressure can be eased in the short term — especially for employees in care, hospitality or retail.

5. Regulation and enforcement for short-term rentals: A transparent licensing system with priority for locals, stronger controls and clear sanctions against illegal listings. Without enforcement every rule remains just a paper in the town hall.

6. Cooperative housing models: Building groups and housing cooperatives can create affordable housing in the long term. That, however, requires support with land access, financing and bureaucratic hurdles.

The difficult balance for politics

All of these instruments affect property rights, tourist revenues and local jobs. Too strict regulation could reduce income in the short term, but too soft a policy could destroy the social substance of the place. Therefore, a package of short-term relief and long-term structural changes is needed, backed by clear data, citizen participation and political backbone. Those who only write appeals will watch the bakery next door gradually close because the owner had to move to a cheaper village. Further aspects are discussed in the article on Rental apartments in Sóller.

What is often missing from the debate

We talk too little about seasonal housing solutions for harvest workers and seasonal staff, about childcare and mobility that make affordable housing possible in the first place. Psychological costs are also missing: people who lose their neighbourhoods participate less in community work, clubs and voluntary activities. Then the tram’s noise becomes only background music to a town without those who fill it with life every day.

An outlook that must not be naive

Sóller is beautiful — anyone who has ever looked from the mirador knows that. But a postcard view alone is not enough. Bold decisions are needed: a rent register, fiscal steering, municipal initiatives to buy properties, supporting social services and strict control of short-term rentals. Only then will the place remain not just photogenic, but livable for people who work here, raise children and run the orange stalls.

In the evening, when the sun casts long shadows over the cobblestones and the tram clatters whistling into the harbour, decisions should not wait. Those who want to act in Sóller must start now — with instruments that protect more than just prices.

Similar News

Drama in Palma: 63-year-old dies after fall in bathroom

A 63-year-old man was found seriously injured in an apartment in La Soledat and later declared dead. The National Police...

Card Payments on Palma's Buses: Convenience or Recipe for Confusion?

Palma's EMT is rolling out card payments across the fleet; around 134 buses already have the system, with full conversio...

Tractors on the island: Mallorca's farmers protest against EU rules and Mercosur

On January 29 dozens of tractors rolled from Ariany and Son Fusteret. The demand: protection for local agriculture again...

Raid in Palma's Prison Ruins: Control Instead of a Solution – Who Helps the 500 People on Site?

A large-scale check took place early morning in Palma's former prison: 160 people were identified and one person was arr...

After property purchase in Palma: What the ownership change really means for cult department store Rialto Living

The historic Rialto Living building has a new owner — operations and the lease remain in place. Still, the sale raises q...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca