Back to School in the Balearic Islands: Families Suddenly Face a €850 Bill

Back to school on the Balearic Islands is noticeably more expensive for many families: around €850 per primary school child, plus extra fees for digital content, uniforms and transport. A look at causes, often overlooked cost factors and concrete solutions from local swap markets to transparent material lists.

School bags, notebooks, uniforms: Why the start of school on the Balearic Islands has become so expensive

On Monday morning at the Plaça de Cort the children's laughter mixes with the clatter of school bags and the quiet sighs of parents. For many families in the Balearic Islands, the bill for the new school year has this year risen to about €850 per primary school child, a noticeable jump compared with last year, as reported in Back to School in the Balearic Islands: Families Suddenly Face a €850 Bill. And while children lick ice cream or walk to school in flip‑flops, parents notice: the backpack is not the only thing that has become heavier.

What is behind the price jump?

Behind the figures lie several drivers. Traditional costs like books, notebooks and materials have increased — publishers are releasing updated editions and additional workbooks, often tied to licensing fees for digital content. The result: what used to be a one‑time purchase is now turning into recurring payments for apps, online platforms or digitally protected teaching materials, as discussed in School start in the Balearic Islands: device bans, new curricula — who pays the price?.

In private and semi-private schools additional items are added: uniforms with the school logo, mandatory sports equipment, sometimes compulsory excursions or surcharges for special offerings. Modern technology — tablets, school apps, Wi‑Fi contributions — also mixes into the list of required purchases. And not to forget: transport costs, after‑school care or supplementary courses can quickly multiply the total.

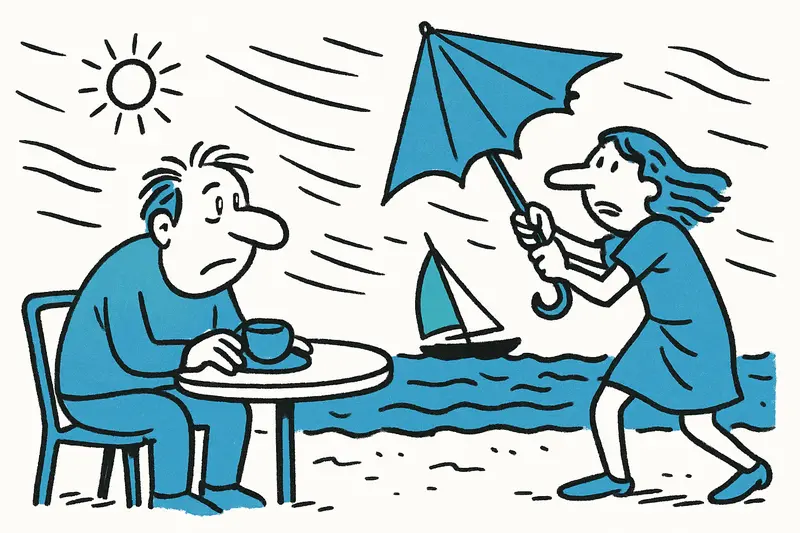

In numbers: families on the islands pay an estimated ten to fifteen percent more than the Spanish average. This is noticeable in Palma as much as in Inca or Manacor — in the heat of September the conversation about prices grows loud at café tables, in WhatsApp groups and in front of schoolyards.

Aspects that are rarely on the radar

Some costs are hardly discussed. Licensing models for digital teaching materials that must be renewed annually are new and hard to compare. Equally underestimated are the hidden expectations placed on parents to take part in school projects or to procure materials for special projects. In neighborhoods like Santa Catalina or around Mercat de l’Olivar the consequences are noticed pragmatically — used book stalls and swap markets are booming.

Social dynamics also play a role: schools with stronger social pressure indirectly create consumption pressures. When parents see others spending money on brand backpacks or new sports sets, the urge to keep up follows — despite tight household budgets. This is a problem that goes beyond simple price comparisons.

How are families reacting locally?

The answers are practical and sometimes improvised, as outlined in Back to School in the Balearic Islands: Around €850 per Primary School Child — What Families Can Do Now. At Mercat de l’Olivar and on the squares of Palma, parents organize second‑hand sales, lists are shared in WhatsApp groups, and swap markets for uniforms appear in Santa Catalina. Schools open storerooms for used books, parent associations coordinate bulk orders, and social funds step in in acute cases.

Still, many families face decisions: do you skimp on extras, postpone purchases or actively hunt for remaining stock? Some admit that where they used to buy new, they now prefer to collect or swap — a pragmatic response to rising costs that nevertheless doesn't remove every worry.

Concrete solutions — short term and structural

In the short term clearer communication helps: early, transparent material lists from schools make comparison and joint orders easier. Local flea markets, scheduled swap days in moderate weather (the milder Mallorcan air helps) and coordinated bulk purchases reduce one‑off costs.

Structurally more is needed: binding rules on mandatory purchases, municipal subsidies for needy families (information from the Spanish Ministry of Education) and the promotion of used teaching materials. Schools could negotiate license agreements for digital content centrally instead of leaving parents to take out individual contracts. A "school start pass" or vouchers for low‑income families would be further instruments that would provide tangible relief in Palma, Inca or Manacor.

The guiding question remains

How much should education cost without overburdening families? The discussion at café tables is serious: education should create access, not new barriers. On the islands, where neighbors help one another quickly, many practical answers emerge — swap markets, social funds, bulk orders. But that alone is not enough. Political guidelines, transparent offerings from schools and the courage to question consumption pressure within the school community are needed.

When the school bell rings in September, it should not only mark the start of a new school year but also signal the chance to resolve the cost question more fairly — so that the schoolbag no longer becomes the yardstick of social inequality.

Similar News

New vacation photos: Royal family in Mallorca — train ride to Sóller and visit to Esporles

The Royal Household has released previously unpublished family photos from the summers of 2012 and 2013 — intimate snaps...

Burger Week and Restaurant Week: How February Comes to Life on Mallorca

Sixteen venues compete for bites and likes: the Fan Burger Week (Feb 16–22) entices with special offers and a raffle to ...

Cause inflammation on contact: How dangerous are the processionary caterpillars in Mallorca — and what needs to change now?

The caterpillars of the processionary moth are currently causing trouble in pine forests and parks. Authorities are remo...

Teenager seriously injured on Ma-2110: Why this night road needs more protection

A 17-year-old was seriously injured on the Ma-2110 between Inca and Lloseta. A night road, lack of visibility and missin...

Storm warning again despite spring sunshine: what Mallorca's coasts need to know now

Sunny days, 20+ °C – and yet the warning system beeps. AEMET reports a yellow storm warning for the night into Tuesday f...

More to explore

Discover more interesting content

Experience Mallorca's Best Beaches and Coves with SUP and Snorkeling

Spanish Cooking Workshop in Mallorca